It was somewhere around 10 km from the Ethiopia/Sudan border that the decision to give away my sunscreen really began to take full force. I say 10 km – I really have no idea. The speedo had said a whimpering goodbye to it intended purpose after 29 km of leaving the city. That soldering job really worked then. But I couldn’t say no to the guy, after all he had opened up his home to me – a complete stranger, with no questions or reservations.

‘What’s that cream for?’

‘Ah. It to protect you from the sun.’

‘The sun? Why?’

– Following the example of Mr Luhrmann, and feeling like trying to explain the value of sun cream to a man of desert life could be a fairly erroneous task, I left it.

‘Can I please use some?’

‘Of course …’

The man didn’t have hands as such – they were rather two giant callouses with a couple of afterthought finger appendages stuck on. The cream would do wonders for those mits, I thought. Liberally applied, it seemed that the man grew somewhat of an instant affinity for the Nivea company.

‘Please can I take this? For my children? The smell is very good.’

Ah, the kids card. A low blow. There was now no way that I was going to be able to prize the bottle for his already-tightening grip. Of course. I’ll make a plan.

And so with the border painfully close, I sat in the middle of the Sudanese desert sun with a nose that glowed blistering scarlet; with two t-shirts wrapped around my hands to stop my knuckles for receiving any more abuse; and with a fully laden motorbike and sidecar that had just come to a unexpected and worryingly shuddering halt. Then no response. This can’t be happening now. Not so close. Not after all this. Frankie-boy, one more push my son, lets get over that border together.

The stage had been set, the situation was as such. The Frank-Alice-Adams, my motorbike and sidecar had been sourced and purchased in Khartoum. We had five days left until our Visas ran out for Sudan. Frank had to be serviced, registered, licensed, insured, equipped and then driven the 580 km across the Sudanese desert from our dwellings in Khartoum and down to the Ethiopian border. We had no way of drawing money, no common tongue with which to converse with any mechanic, lawyer or admin jockey, and a list of undisclosed mechanical problems that left Frank pitifully whimpering on a ICU machine. Matt and Jimmy had to get out of the city sharpish in order to allow enough time to cycle the sun drenched distance before we officially became illegal wanderers in a country where you really don’t want to have the administrative headaches of explaining such a lack of legality.

Five days until Visa runs out:

Wake up to a completely flattened rear wheel. Oh, you bastard. So it seems that the new inner tube that was apparently just put in seems to have the ageing quality of a pear. Next to address the worrying oil leak from the right piston. Then the oil pipe breaks. Off to a promisingly unpromising start.

Four days:

So the oil leak from the right piston apparently can’t simply be forgotten about or solved with a quick wipe down with a cloth. Wishful thinking. Frankie requires a significant transplant. Two brand new pistons are the order of the day. The new ‘grinding’ sound from the engine, I’m informed is not ‘as-common-with-every bike’ as I originally have been lead to believe.

A marathon twelve hour straight mechanical stint begins; sitting on the oil drenched concrete floor, mishearing and misinterpreting the barrage of torrential information; the do’s-and-don’ts, the hit-this-tighten-that-check-everythings that one legged Sudanese mechanic barks at me. The engine is taken apart. The new pistons need go through the process of ‘selection’ – I am told this will take two days. This is not ideal – I still haven’t driven the thing. Or any motorbike, come to think of it.

Three days:

‘What do you mean my whole passport has to be translated into Arabic?’

Not an all too frequent requirement when the vast majority of secondhand motorbike sales are performed. So off to the university to search for a spectacled professor and a stamped translation. It seems that google translate does not hold official credibility, much to my demise. We complete the reams of paper pushing, licensing, registration and other bureaucratic hot-stepping half an hour after the traffic police headquarters closes. The tides of lady luck may just be turning – I am the official and legal owner of a Sudanese/Czechoslovakian motorbike. That’s dating it. Crisis.

Then back to the mechanic workshop for get more cross legged teachings. Another 8 hour stint.

I drive Frank for the first time across a Khartoum in rush hour. Subsequent breakdown. The exhaust backfires two kilometres from home. I loose all confidence in the bike and my bid to escape together. Moral hits rock bottom. The mechanic is called out to the side of the road once more. The ensuing solution to the problem simply highlights my naivety. Up is not the same as down on the fuel switch; I have run the reserve tank dry. The backfire is a result of frighteningly over-heated engine oil. A very valuable lesson is learnt; firstly, Thomas you are an idiot. Secondly, the problems are not wholly with the bike but rather with personal insufficiencies. A simple flick of a switch and we’re off again.

Two days:

The pistons, I am told should be ‘okay’, but only if I keep to a strict 50 km/h. Today I need to leave, another days delay and it would have to be a 12-hour-straight dash to the border. Seeing as I have only ever ridden Frank for a collective of 20 km, this would be out of the question. So with an appallingly ill-pack sidecar filled with numerous objects of unquestionably useless merit, strapped on at any and every angle with any piece of material with a degree of elasticity to it, I said my fondest fair-wells to my newly adopted extended family and headed for Ethiopia.

Half a kilometre covered. Just need to top up on oil and petrol. Try to re-start the engine; a complete lack of power. Frank stubbornly refuses to get out of first gear. This can’t be happening. It seems that the vice of illegitimate wandering is slowly tightening its grim grip on me. There’s no way this bike can make it. Half a km.

Stay calm, and think. What did the one-legged mechanic say again?

Check spark plugs. That’s it. That I know that I can do.

This is surely the problem. They are smothered and covered in carbon – there must be something wrong with the combustion? Maybe the petrol/oil ratio? Maybe that and more? If only I could talk to a mechanic who spoke English. Hang on; if only I spoke Arabic. Lets remember where we are.

I sand them down. A technique that will be honed to a fine art in all to short a period of time.

Power back up. Lets go now – lets go, and not stop for a long time.

At least the brakes work – I have to slam them on as the articulate lorry carrying livestock, and so safely equipped with not one, but no brake lights stops without warning on the bridge. I swerve dangerously to the side and into the lane of the on-coming traffic. Luckily there’s no traffic. I’m following too closely – I don’t know this bike yet, and I need to be patient. Lesson learnt. I’ll chalk that one down as strike one.

29 km – off packs the speedo. You shameless deserter – I needed you, you coward. That 50km/hour limit is going to be complete guesswork now. The effects of the antimalarials is now also joining the party and causing it own cameo of problems.

Doxicycline: WARNING – ‘some individuals might experience discomfort when exposed to extreme sunlight. Side effect – skin can become increasingly sun sensitive, could lead to serious burning to overexposed areas.’

The cuticles of my fingernails are burning. My cuticles. And the knuckles. And my nose. I start to have a fierce nosebleed – it must be from the sunburn. I carry on for a bit. My beard becomes saturated scarlet. If the police pull me over now, this could take some explaining. ‘No officer, that last piece of road kill wasn’t a result of my hunger.’ I look mildly deranged. 200 km down though. Frank is is excelling on the effort front – the achievement is still to be validated.

Its now six o’clock. That’s been seven hours riding on the road, and Frank has once again completely lost power. Fortunately I have temporarily broken-down on the curtails of a little village. I push and pull the bike to a little patch of the least uneven terrain and plan to get an early night in Barnabas.

The crowd emerges even quicker than I had expected. The kids have a football – the ensuing game confirms the fragility and enduring weakness of my right knee. Then the elders converge. Like countless times before, the problems associated with my chosen dwelling are completely concerned with my own comfort and safety.

‘No, no. Come with me. You must take my bed. I have food. You look dirty. Very dirty. Come wash.’

My confidence regarding my newly improved safe dwellings takes a significant blow as 6ft black cobra wrapped around a stick is marched out of the house. Something about the courier’s hurried passing indicates that this might not be a domesticated pet. I watch closely as he disappears into the bush. Walk far, brother.

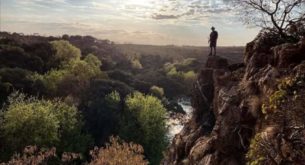

Sleep comes surprisingly easily; a brilliance of dark and diamonds above heralding in the promise of another morning of eventful adventure. We are half way there. 280 km down.

I lose my sun cream to the callouses and the kids.

Visa expires today:

My alarm clock is as unexpected as it is mesmerising. A collective of 200 strong Sudanese police men are out for their early morning training run. Their unionised voices lifting up and over the rising dust cloud of their making. The morning licks of ambered glowing giving an altogether surreal resonance to this iconography of sight and sound.

I pack up quickly. I’ve learnt my lesson all too conspicuously of the ills of riding through the high heat of the day. Right Frank, lets be off. An hour later and I’m still muttering the same sorry expletives. Suddenly life; go, go. I get out of the village and weave my way through the throngs of quite rightly curious voyeurs.

Half a km covered. Power down again. Again. The tide is ebbing slowly away from me; somebody doesn’t want me over that border. Right, spark plugs – my go to remedy. I seems to work. Frank crawls away for the village once more; but a crawl is better than static. 300 km or so to go. Its already getting hot.

Frank starts purring. Purring is a very subjective term.

We push for six hours; taking no more than half-an-hour’s rest. Stopping could be disastrous; I’ve already learnt that Frank thrives on momentum. Are we good on petrol? Yeah, I think so. Carry on.

The kilometres drop by. My smile is growing, as is my mild feeling of dehydration. This machine, despite its seemingly innate ability to frustrate is this most exceptional promoter of childish happiness. The freedom and self-reliance that I longed for during those months of sourcing and setbacks has returned in full force.

In fact, it seems that I haven’t bought a motorbike but rather a facilitator of extraordinary interaction and a focus of collective and collated effort. It just so happens to be made of a jumble of steel, rubber, and a healthy volume of electrical tape. But a jumble of unparalleled character; a quality that certainly adds a huge amount of colour to this whole process. This is opening up a whole new world to us; the world of the mechanically challenged and the permanently oily handed. A world that we are relishing. Frustrations, breakdowns, and all.

The wealth of inquisitive come questionably qualified eyes and hands that have diagnosed, sourced, and serviced has already been a tall example of human kindness and generosity, irrespective of payment or prior communication. Getting to know a country through its mechanics and fixers, framed with the seemingly endless need to overcome a presented problem is a particularly unique insight. One that continues to be an extraordinary experience and privilege. The prevalent attitude toward problem solving is truly inspiring – nothing is too much of a problem. The optimism is ripe and infectious. If Frank makes it all the way to Cape Town and doesn’t finally give up the ghost in the way, it will certainly be a result of a special mix of persistent goodwill and the ingenuity of a continent that is defined by its remarkable ability to adapt and to survive whilst constantly wearing a smile.

And so, with the border looming and the prospect of our team reunion imminent, this was not a phone call that I wanted to be making;

‘Ah good man, about 10 km to go I think? Slight problem though. Might have just run out of petrol?’

In fact in wasn’t petrol that I had run out of, but rather the ability to think rationally. Flick it to the reserve tank you muppet. Like so many instances, the remedy once more proved to be a combination of common-sense and constructive self-criticism. With the simple flick of a switch Frank was purring once more. Up over the hill, and then down to the border town – we had made it. 580 km on green pistons and an even greener rider. Well done you old communist war horse, you.

Now to get it over the bridge and into Ethiopia.

At a customs post, the last thing that you want to hear are the following words, especially when your visa has run out;

‘There is absolutely NO way that you are going to get that bike over the border without the right paperwork. You need a carnet. It’s impossible. Impossible.’

The prospect of driving all the way back to Khartoum to pick up one piece of paper, to subsequently enter a country that you have been reliably informed by the head of Khartoum traffic police doesn’t require said piece of paper was out of the question. So buoyed by our reunification, but dismayed and exhausted by yet more bureaucratic demands we went to seek a nights solace on the dust and rubble of the Sudan police station’s garden.

At least we were in a continent were impossible is nothing. There was certainly a solution, we just had to wean it out of the right customs official. Come the morning we were officially illegal wanders, a thought that sent us into a fractious sleep.

The morning of wandering illegality:

The fact that we had to push Frank to the bridge was not a overly confident start to the day. No response from the engine. What is wrong this time? Take your pick. The list is bountiful and worryingly expansive. Ah, we’ll deal with that, or those once we are officially over the border. Maybe ‘if’ is a more appropriate term.

It is always an amazing spectacle to witness the carefree informality of officially formal processes. In walked our hope and saviour in getting Frank over the bridge. A young official, dressed in jeans and a t-shirt. As we sat in that tin roofed house that bore the title of Ethiopian border customs, it seemed that the declaration of ‘impossibility’ was rapidly fading into redundant obscurity. No new paperwork was required, no phone calls made, no carnets, no import duties. It seems that the letter that I got from the South African embassy in Khartoum had proven to be our golden ticket. An official letter head, a sniff of foreign embassy approval, and an official stamp was all that was needed. Well that, and a photocopy of my now expired Sudanese Visa. Frank had his papers – he was into Ethiopia. We had escaped? This was all too easy. Something must be wrong.

With a hope-filled final swagger and a roll we once more hopped our way over the bridge to get ourselves stamped out of Sudan. Frank was over, no worries. Stamped into Ethiopia, no going back now. One more piece of paperwork and then all would be smiles and free to go.

One of the most telling characteristics of optimism is that it can so easily be shattered. A decidedly pissed off looking Sudanese border official standing over your motorbike on the bridge between two countries will certainly provide this shattering effect. Clearly working under the delegated pressures of angry superiors this poor sod had been given the task of demanding that Frank be taken back over the bridge and into Sudan once more. It seems that in our haste we had, either intentionally or not skipped Sudanese border customs and now found ourselves in serious violation of international customs regulations. With much demonstrative arm waving, finger pointing, and throw downs of an increasingly battered looking beret, Frank’s Ethiopian customs papers were removed from our grip and folded into the back pocket of a pair of faded jeans. Oh dear. This could spell the end of this little motorbike shindig. So once more, and now under burningly stern official scrutiny we once again pushed Frank back over the bridge. Our escape into Ethiopia had lasted no more than half-an-hour.

Sternly told to sit there and wait; and not cause any more problems.

‘Your licence, and frame/engine numbers have not been cleared. You are NOT allowed to go over to Ethiopia! You must stay here in Sudan. Very bad.’

In fact Sir, they were checked yesterday by Mohammed, he has done all of the paperwork. Who?

‘You know Mohammed, the swarthy looking one with the cheeky little mooshy.’

The look on their faces suggested that they didn’t know that Mohammed, despite how cheeky his mooshy might be. They become disinterested.

An hour later in swans the very owner of the mooshy in question:

‘Oh, that Mohammed! Of course, no worries about your paperwork. Everything is fine. You’re free to leave … wait, come have lunch with us first.’

The beautiful simplicity and invaluable merit of having the right stamp-makers on your side.

And so, for the final time we headed back over the bridge. The back pocket document was unfolded, already looking seasoned. In wonderfully inglorious style Frank is pushed over the official border line; and faced immediately with a hill. Frank has never seen a hill before. And I had forgotten that it had refused to start this morning. First task; lets find a yet another mechanic …