Lucy Corne looks into a big, murky hole and uncovers an incandescent history with lust for adventure and fortune at its core.

Words: Lucy Corne | Photography: Lucy Corne, gallo images/alamy, gallo images/Getty, Shutterstock

From the unearthing of the first gem in 1871 to the end of the diggings in 1914, The Big Hole produced almost 3 000kg of diamonds.

Peering over the barrier into the depths of the hole, I try to shut out the chattering of fellow tourists. I squint to blur the buildings and cars in the background and attempt to imagine this enormous pit as it once was. Once upon a time, instead of being filled with 22 fathoms (41 metres deep) of opaque, jade green water, it would have been filled with hundreds of diggers in desperate search of diamonds. That was 150 years ago this July, when ground was first broken for Kimberley’s Big Hole.

It wasn’t always a giant hole, of course. When diggings began in 1871, diamonds were being found fairly close to the surface. But with even the strongest squint and the best imagination, it is impossible to imagine that Kimberley’s famous hole actually began life as a hill, known at the time as Colesberg Kopje.

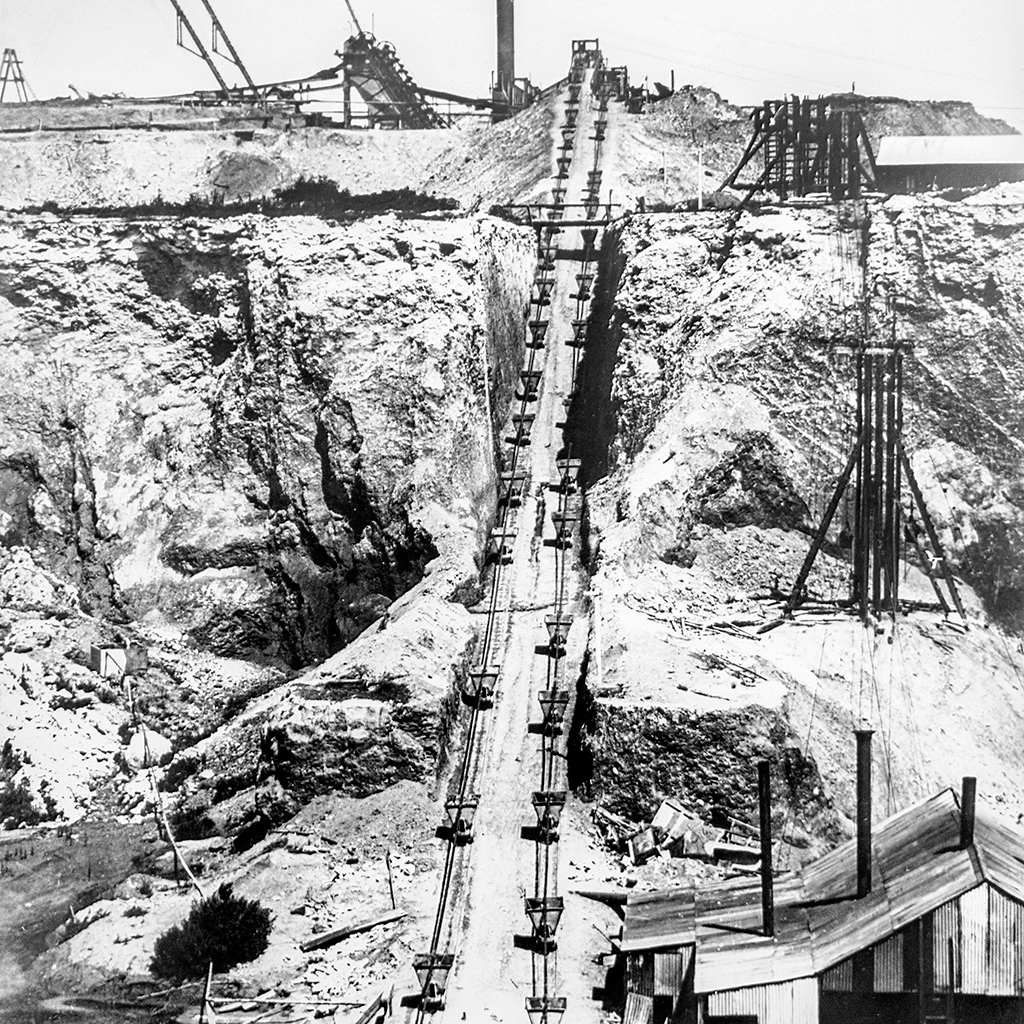

Headgear was first constructed at the Kimberley mine in 1890, allowing miners to haul kimberlite rocks from beneath the surface.

Fortune seekers had flocked to South Africa from around the world following the discovery of the Eureka diamond in Hopetown in 1866. But many found that Hopetown delivered nothing more than hope and they soon moved their shovels and picks to Colesberg Kopje, found on a farm 125km northeast. The owners of that farm were the De Beers brothers, whose name would forever be associated with diamonds. The kopje did not enjoy a similar longevity. ‘Gradually the round hill was whittled away until it was level with the earth,’ writes James Leasor in his book Rhodes & Barnato: The Premier and the Prancer. ‘Digging continued until what had been a hill became an ever deepening hole.’

New Rush

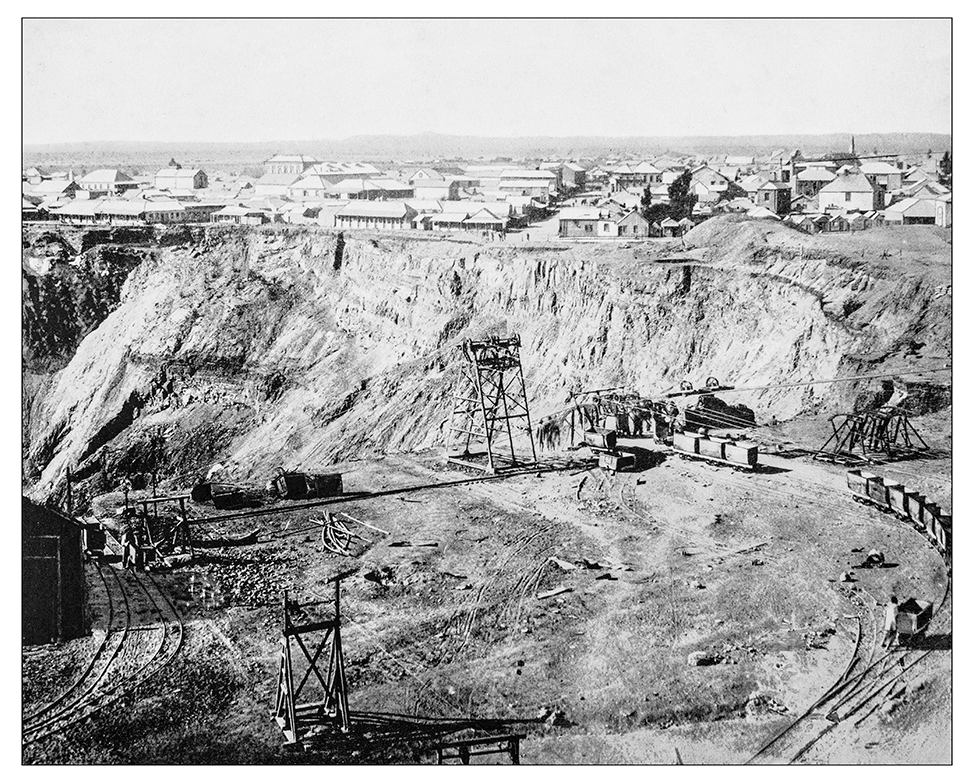

Today, that hole is 215 metres deep and is the main attraction in the Northern Cape’s capital city. The Big Hole is where Kimberley began, although back in 1871, the town went by a different name. Thanks to the influx of diggers hoping to get lucky, the rapidly expanding settlement was given the moniker ‘New Rush’. Starting as a makeshift tented camp, New Rush quickly morphed into something more permanent. By 1873, it had a population of more than 40 000 – the second largest settlement in South Africa at the time. Tents gave way to corrugated buildings, with all the town essentials in place: supply stores, banks, churches and many, many bars.

The mock up town at The Big Hole is a blend of reconstructions and rescued artefacts.

It is in one of those bars that our visit to the Big Hole begins. Well, okay, not one of the original bars, but it is certainly inspired by them. The Occidental Bar is part of the mock-up diggers’ town that skirts the Big Hole complex. Slightly cheesy but somehow quaint, the town features corrugated buildings meant to evoke the era – there’s a saloon, a bunch of stores, a church and even a bowling alley. Sadly, it all feels half-done, since most of the buildings are mere facades and those that you can enter largely contain nothing more than faux artefacts or mannequins the ilk of which you’d normally only see in a horror film. But it does a decent job of setting the scene for the tour we’re about to take.

Our guide at the Big Hole is David Tlhabanelo and he is marvellous. He has our group giggling, gasping and hanging on every word.

And he’s not the only person we ‘meet’ that day with whom we feel it would be fun to share stories over a pint – although the other has long since departed. Guided visits to the Big Hole kick off with a 20-minute video that tells the story of the first diamond discoveries, the development of New Rush and introduces two characters whose success was intertwined with that of Kimberley: Barney Barnato and Cecil John Rhodes.

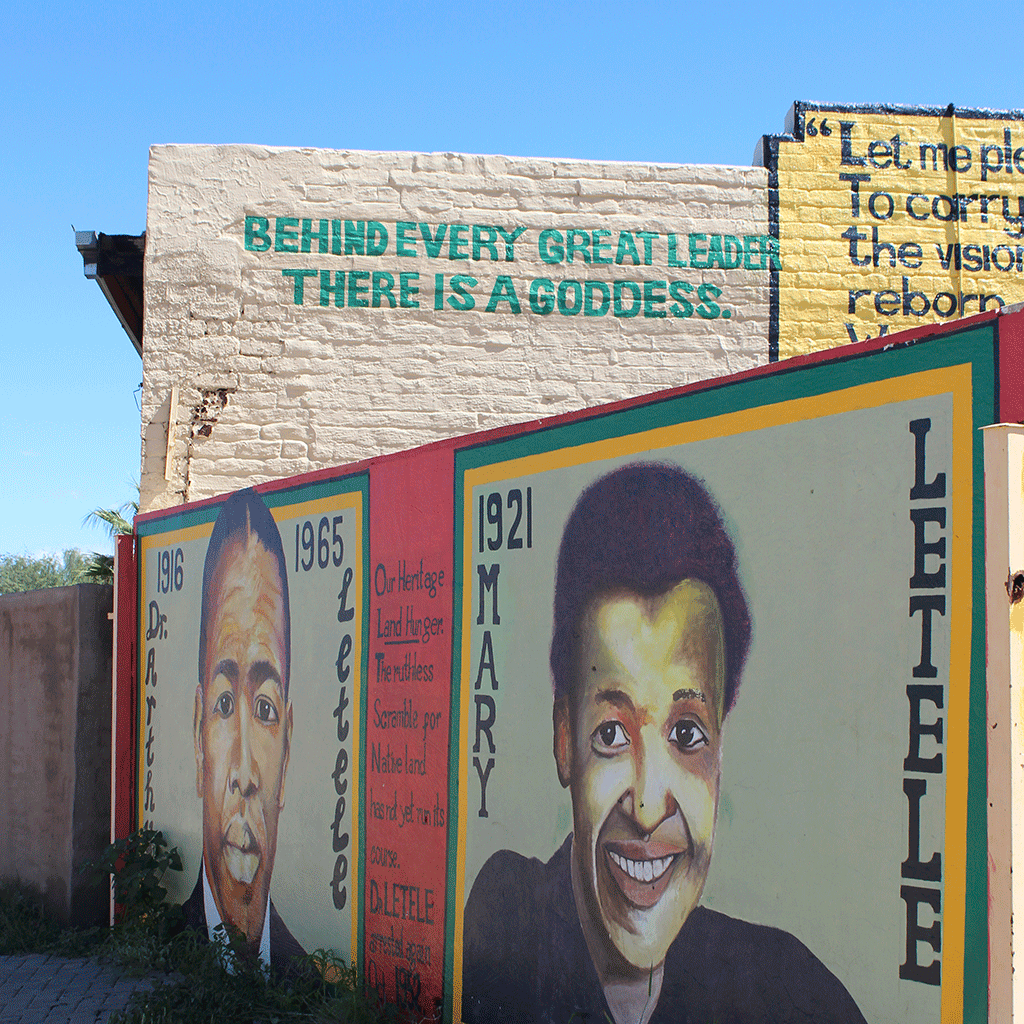

A mural at Robert Sobukwe’s old law office in Galeshewe celebrates struggle hero Dr Arthur Letele and his “goddess”, Mary.

The odd couple

As a sickly teenager, Rhodes had been prescribed a long sea voyage and he set his destination as South Africa. But he wasn’t interested in rest and recuperation – his sights were on riches, politics and conquering a continent. Barnato is less well known but, to me at least, much more likable.

A smart-talking wheeler-dealer from the east end of London, he’d arrived in South Africa in 1873 with little more than a suitcase of clothes and some cigars to sell. A natural charmer and born salesman, he grafted and hustled and was a millionaire by the time of his mysterious death at sea at the age of 46.

I’d never heard of him before visiting the Big Hole, but I instantly liked the sound of Barney. Rhodes would not agree.

Although it began as an open surface mine, once the claims stopped producing diamonds, underground mining began.

While the two often met and ultimately worked together, their outlook on life couldn’t have been more different. Rhodes was serious and stuffy. He had no time for frivolities and was said to have looked down on Barnato’s impoverished upbringing. Barnato, by contrast, was the class clown – a likeable joker always ready for a night out at the New Rush taverns. He was also in no small part responsible for Kimberley’s success – and for the creation of the Big Hole.

Following a few years of digging, the finds were becoming less abundant and the diggers were packing up their picks to move on. But Barnato insisted they’d only scratched the surface – literally – of Kimberley’s diamond stocks. He bought claims containing only ‘blue ground’, ground previously thought to be devoid of diamonds. It turns out Barnato was a bit of a visionary. The blue ground gave up its riches, with Barnato – and Rhodes – reaping the rewards.

Cecil John Rhodes (left) and Barney Barnato had very different outlooks on life, but in 1888 they merged their companies to form De Beers Consolidated Mines.

Lost lives and found fortunes

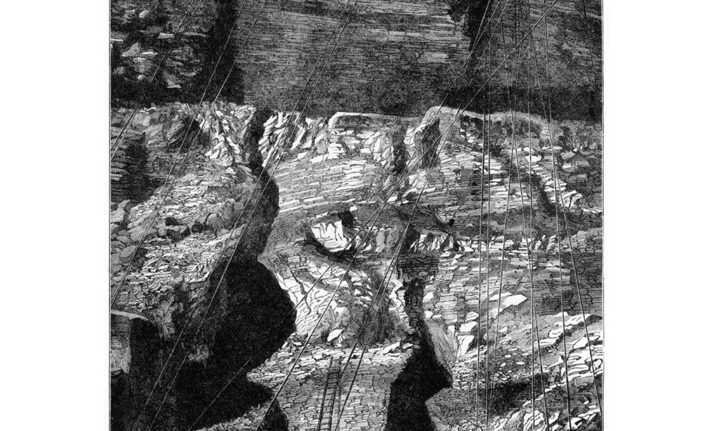

To understand how a surface mine morphed into this deep pit, you have to explore the museum – best visited before venturing to see the hole itself. You’ll need an hour to do it justice but if nothing else, check out the images of the Kimberley Mine in its heyday. Vertiginous pathways lead between the claims, all being dug at different depths. A mystifying web of ropeways hover above, with precariously placed ladders dotted around for a bit of extra danger. Later on, underground mining began and eventually the whole network of carefully chiselled claims started to erode, collapsing into one colossal hole.

Today, the Big Hole is the city’s main attraction and unofficial emblem. Locals seem to love it and loathe it in almost equal measure. They love that the colour of the water alternates between blue and green with the changing seasons. They’re not so fond of the fact that the busy Bultfontein Road, skirting the eastern edge of the hole, has been closed for more than a decade for fear the thundering trucks might cause a cave-in.

You can get your moustache trimmed to resemble Barney Barnato’s at the hairdressers in New Rush.

As my tour group heads back to the mock-up old town, I take a few more moments to gaze out at the hole. Today it’s a peaceful beauty spot, but it is here that lives were lost and fortunes were made. When mining ceased in 1914 it wasn’t due to a lack of gems, but because World War I started and I can’t help wondering how many diamonds still lie beneath that strangely beguiling water.

I end the day with one last wander around New Rush, trying in vain to picture this place as it would once have been – dusty and primitive, with businessmen and conmen, labourers and ladies of the night all bragging about their finds in smoky saloons, an air of hope enveloping them all. I’ve always had a fascination with the Wild West but, following a few days in Kimberley, I realise you don’t have to travel to the American frontier for tales of swashbuckling adventure and a dash of pioneering spirit.

Being a diamond digger was a life-shortening business. Conditions were unsanitary and dangerous, with thousands dying from disease or mining accidents.

Kimberley curiosities

A miraculous rescue

Ducks are sometimes seen swimming in the Big Hole, but imagine locals’ surprise when in 2013 they spotted a dog doing laps. The pup remarkably survived the fall then spent a full week of paddling the perimeter, intermittently resting on a ledge. The dog, nicknamed ‘Captain’ when singer Kurt Darren offered to pay for a helicopter to assist in the rescue, was later adopted by his rescuer, police officer John Seeley.

A record breaking hole?

Google maps describes the Big Hole as a ‘massive hand-dug diamond mine pit’ – a to-the-point description if ever there was one. Authorities had long said that this is the world’s largest hand-dug hole, but, in 2005, a local historian presented evidence that a mine in the Free State, the Jagersfontein hole, could actually lay claim to that title. Google’s description still stands though. It might not be the biggest, but it sure is massive.

Gateway to the…north?

Rhodes’ ultimate goal was to build a railway from Cape Town to Cairo, spreading British rule and influence north through the continent. But legend has it he wasn’t always sure exactly which way north was. A founding member of the Kimberley Club, Rhodes would reportedly wax lyrical about his plans for African domination while flamboyantly pointing in the wrong direction. An iron arrow set into the stoep of the club is said to have been put there to aid him in his gesticulations.

The Big Hole’s mock-up old town takes its name from the original diamond digger settlement, New Rush, which was renamed Kimberley in 1873.

Stay Here

Kimberley Club

Founded by Rhodes and his cronies in 1881 as a gentlemen’s club, this boutique hotel has elegant guest rooms – some of which are said to be haunted.

From R1 000 per person sharing.

053 832 4224, kimberleyclub.co.za

Protea Hotel Kimberley

Perhaps the best-placed hotel in town, with views of the Big Hole itself. The lobby is a veritable museum to Kimberley’s past. From R948 per person sharing.

053 802 8200, marriott.com

75 on Milner Lodge

In a central location close to the Honoured Dead Memorial, it’s a friendly spot with well equipped rooms, hearty breakfasts and a pretty pool area.

From R850 per person.

082 686 5994, milnerlodge.co.za

Do This

McGregor Museum

Housed in the old sanatorium where Rhodes holed up during the 1899 Siege of Kimberley, this excellent museum charts the city’s history. Adult/child R25/15.

053 839 2700, museumsnc.co.za

Magersfontein

This Anglo-Boer battlefield was the site of a bloody victory for the Boer forces in 1899. There’s a small museum but it’s best visited with a passionate local guide such as Frank Higgo. 082 963 6657

Galeshewe

A tour of Galeshewe introduces you to a different era of local history. Stops include the site of the 1952 passbook protests, Robert Sobukwe’s office and the house where he lived out his post-prison days. For walking or cycling tours, contact Native Minds.

053 871 3690

The Big Hole

Tickets include a short film re-enacting the early diamond diggings, access to the exhibition and an entertaining guided tour above and below ground. Access to the old town is free. Adults R100, children R60.

053 839 4600, thebighole.co.za