Part barbarity, part act of love. It’s a bit like watching someone you care for go through an amputation: you know it’s for the best but that doesn’t make it any easier to watch. Alan Valkenburg went to Pilanesberg to witness a rhino dehorning.

The baby rhino made her way along the dusty dirt road, sprinting as if her life depended on it. For all she knew, it did.

She’d just witnessed her mother being darted and now the noisy flying machine was chasing her. No taller than a medium-sized dog, she was small but solid; one day she would pack the power of a tank. Right now, though, she was just a tiny baby, squealing in terror.

The chasing chopper dipped its nose, increasing the volume and spray of dust, the tumult from its rotor blades creating in the rhino a blind panic. As she rounded the corner, the telltale pink fluff of the tranquiliser dart protruding from her rump revealed that she, too, had been darted. She wouldn’t be on her feet much longer.

We stood watching this unfold, a posse of four journos, guests of Toyota for two days of behind-the-scenes insight into rhino dehorning in Pilanesberg National Park. The car manufacturer has over the years ploughed several million rands into conservation, not only donating money and raising sponsorships to protect rhinos and other wildlife but also by donating a vehicle or two – and then offering service plans with no apparent expiration date.

We joined the anti-poaching unit willingly, of course, but what we witnessed was not pretty. After all, these guys do what they can to make rhinos as unattractive and unappealing to poachers as possible. What was clear from the experience, and from speaking to everyone involved, is that this was not just a PR stunt. These people do what they do because they care.

The team included veterinarian Gerhardus Scheepers, who went to great lengths to stress that what they were doing was not painful to the rhino (and did not affect them socially either). There was volunteer and helicopter company owner Wessel Wessels, who spoke with passion and a real pain in his voice about the lack of humanity that would allow a human to butcher an animal so brutally for its horn. And there was Toyota’s John Thomson, who spoke about how his granddaughter sits on his lap while he photographs game and how he ponders whether her children will ever get to see a rhino. Each member of this team was there with a single-minded purpose: to save rhinos.

Sawing and grinding

When we caught up with the dehorning squad it was past midday on their fifth day of operations. There were two teams on duty, each comprising a veterinarian, a helicopter pilot, park rangers, interns and rhino anti-poaching unit members.

A third vehicle, driven by John and Wessel, transported extra fuel for the helicopter and other extra provisions. Our media vehicle followed one of these teams. We were soon in the thick of the action as the helicopter radioed us to say, ‘Rhinos spotted.’

While our convoy of vehicles hurtled along dirt roads – often with a few wrong turns and many seven-point turns along the way – to get nearer the rhino’s location, vet Gerhardus darted the rhino (or rhinos – sometimes they were in pairs) from the helicopter. Which meant we needed to get there quickly.

The chopper pilot would then “encourage” the drugged rhino to stay close to a road (by dipping low and making a nuisance of himself), making our job easier.

We’d arrive on the scene to see a visibly punch-drunk rhino stumbling around like a dog in socks. Once the rhino toppled over, our group would approach the animal, the team setting to work with military-like speed and precision.

We were warned to stay away from the dart entry point and any blood as the dart contained M99, a morphine-like substance thousands of times more powerful than anything that goes into human bodies. ‘One drop of that and you’re dead,’ we were told.

That was fine, we were more interested in what was happening at the rhino’s other end.

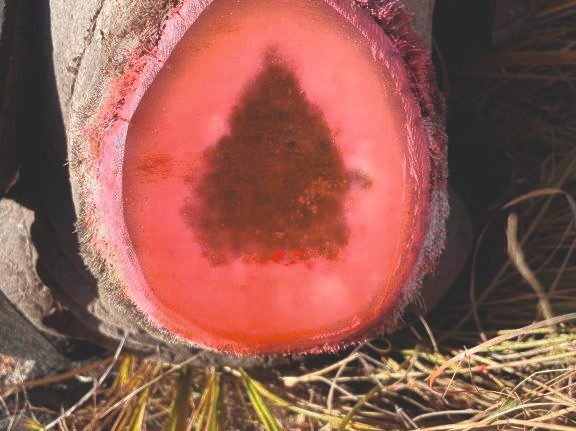

With a blindfold cover placed over the rhino’s face, Gerhardus went straight to it, taking out an electric saw and putting it straight to the horn. He had to be careful – cut too low and not only do you risk injury and infection, there’s also the risk of damage to the horn plate, meaning the horn may never regrow.

What I learnt is that a rhino’s horn isn’t fixed to the skull, it’s almost an extension of the skin (similar to a person’s fingernails). This is of course a source of great consternation to the anti-poaching team and we were told on more than one occasion that poachers have absolutely no need to kill the animal to remove the horn, they just do so because it saves time.

Sawing through the horn was hard work – they’re thick and the rhinos would sometimes move. But Gerhardus cut straight and the job was always completed within two minutes.

The second horn followed the way of the first, but if we thought the noise of the saw was bad, the angle grinder that followed was worse.

‘Why the angle grinder?’ we asked. ‘To prevent splitting on the stump plate. Sometimes the rhino will bump against a tree or something else and the stump will split, which leads to other complications. This helps to prevent that.’

Once the grinding was finished, John moved in with his F10 wound spray, a pink antiseptic that he used on the stumps, rubbing it in to prevent infection, before he administered eye drops to the creature in case any stray bits of horn debris had blown into its eyes during the sawing process.

While all of this was going on, other team members had been administering deworming, multi-vitamin and anti-inflammatory injections (because the way the rhino falls can cause an injury). Meanwhile, others tagged the rhino’s ears and inserted or checked radio transmitters.

There was usually time for a quick photo before park ranger Steven Perry ushered us away as the “wake-up drug” was administered. Within minutes the rhinos were on their feet, no doubt asking each other, ‘Do I look different to you, Susan?’

We went through this procedure a few more times that day and the cutting of the horns was always hard to stomach. John had told me how he’d seen grown men reduced to tears watching it – seeing that saw battle its way through the horn made for uncomfortable viewing, and triggered memories of a botched wisdom tooth extraction during a fateful trip to the dentist some 30 years ago. Necessary, but horrific nonetheless.

Our mission to the Pilanesberg was quite hush-hush and it had to be. Park rangers and the anti-poaching unit guard rhino information closely and even questions about the park rhino numbers are met with a smile and a shake of the head as if you’re a child and you’ve just asked an adult visitor to your house “How much money do you have?”

Such secrecy is critical: no one wants to put up a sign saying, “Here be plenty of rhinos.”

And we were asked to commit to that secrecy, too: no posts on social media, no publishing of any details of what we’d experienced, for several days. Media silence would give the team time to finish its work, pack up and clear out. We were happy to oblige. A kilogram of rhino horn averages $8 700 and there was a vehicle driving around with several of them. In the immediate aftermath of our escapade, those horns were moved to a secret location where they’ve been carefully logged, measured, weighed, tagged, chipped and DNA sampled before being placed in storage.

Fly, baby, fly

But, what about that baby rhino? The little lass was reunited with Mom. How this was done was a complicated process because she had run hundreds of metres before collapsing and, in this thick bush, she may have taken days to find her mom again, if at all.

So it was that the anti-poaching unit lifted her onto a stretcher and carried her to the helicopter (it took about six of them), before strapping her in and airlifting her to a spot closer to her mother, where she was released and woken up safely for a happy reunion.

Chip in

The process of protecting rhinos is costly. Anti-poaching units, dehorning events, and raising baby rhino orphans (as a result of poaching) all cost money. A great way for companies to help and participate is through dehorning and notching events. Revenue raised is paid into trusts that support rhino conservation. They’re also great team-building or customer event days and can be arranged via the trusts.

Donations can be made to the Pilanesberg Wildlife Trust via its website (pilanesbergwildlifetrust.co.za) or to the Zululand Conservation Trust (zululandconservationtrust.org).

There are also fundraising events such as the Pilanesberg and Manyoni runs, cycle races and golf days.

The Madikwe Wildlife Foundation offers funding for rhino, wild dog and lion work or you can donate to Rhino Pride Foundation (rhinopridefoundation.org), Care for Wild (careforwild.co.za) or Rhino 911 (rhino911.com).

A version of this article appeared in the September 2022 print issue of Getaway

Words and photography: Alan Valkenburg

Follow us on social media for more travel news, inspiration, and guides. You can also tag us to be featured.

TikTok | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter

ALSO READ: Reptiles in the suburbs