During a birthday celebration diving adventure, Alexandra Torborg and a group of freedivers have an extraordinary encounter at Aliwal Shoal, off the KZN South Coast.

Photos: Linda Ness, lindaness.co.za

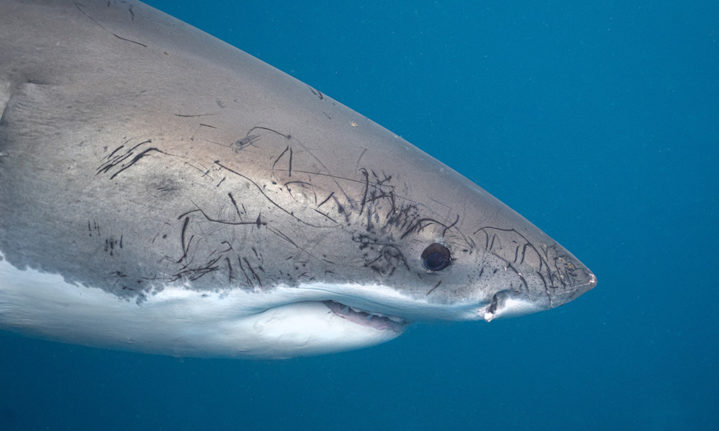

Great white sharks are sometimes accompanied by remoras, otherwise known as sharksucker fish. They attach themselves to sharks, rays, whales and even scuba divers using a modified dorsal fin that acts as a sucking disc. The fish feeds on food scraps from its host or parasites on the host’s body.

Dropping off our inflatable dive boat into the water at a spot called Chunnel on Aliwal Shoal, we were surrounded by sealife activity: schools of shoaling fish; green, loggerhead and hawksbill turtles; shorthorn devil rays and white-tipped reef sharks were swirling all around us. A pod of bottlenose dolphins swam by, looking intently at us before disappearing. With little current, we could spend a lot of time in the same area enjoying the inter-actions. On other days, this spot is called the ‘Aliwal Express’ when the current is so strong you can drift 5km across the length of the shoal in 20 minutes.

Back in the boat after our amazing sightings on the reef, my friend Natalie was surprised when we produced a cake and sang happy birthday to her. While everyone munched away, Cassie Weinberg, our skipper and owner of Wetu Safaris, cruised south of the Shoal to a spot where we often find tiger sharks, on their summer visit to the KZN coast.

This species is curious but incredibly shy, and the key to swimming with them is to stay calm so as not to scare them. Our group of experienced divers was swimming near the surface when two tigers came to inspect us briefly, then swam away. We knew the drill – stay still, don’t flap your fins about, and wait for them to return. Then, out of the blue, a much broader shark came swimming towards us. I’d always wondered previously if I’d recognise a great white shark (some can be difficult to identify). But yes, this one was unmistakable.

I immediately started filming with my GoPro, thinking it would swim by and disappear. It passed us very slowly and deliberately, then turned back to look at us. I was transfixed by its large black eye. When the light caught it, it changed to a deep blue around the pupil. The shark swam slowly on, then turned to approach us again, and again, getting closer each time. Everyone stayed calm and moved closer together into a huddle. We watched in awe, and some trepidation, as the creature circled us. After about the fourth time, we decided it was time to get out of the water.

By remaining as calm as possible, this group of freedivers were able to enjoy an opportunity of a lifetime: sharing the water with a great white shark.

We signalled to Cassie in the boat, who didn’t know there was a great white in the water until he pulled up alongside. Keeping eyes peeled on the shark we tried to exit from the water without too much splashing.

I’ve never heard so many expletives at once as we sat there stunned, not believing what we had encountered. ‘This is an opportunity of a lifetime,’ Cassie said. ‘Get back in the water.’

I responded with: ‘Cassie my cup is full – that was enough!’

Two of our group, however, slipped back into the water while the shark continued to swim around the boat, from where we watched our friends nervously. I admired their bravery, particularly when the curious shark got extremely close at one point. Their cue to get back in the boat.

We took a quiet moment together, gave thanks to the ocean and the magnificent shark for this incredible experience. Andy expressed the sentiment of all of us with a ‘Siyabonga!’ as he raised his hands with gratitude. We couldn’t stop smiling on the return trip to shore, a mixture of joy and numb disbelief. I don’t think any of us slept that night. The elation persisted for days, with all of us playing the scene over in our heads since that remarkable encounter.

Great White Behaviour

Our perception of this species has been influenced by films like Jaws which falsely portray sharks as vengeful creatures. Here is a more balanced analysis on how they react to humans, and how they migrate along our coastline.

Alison Towner, a white shark biologist with Rhodes University and the Dyer Island Conservation Trust, looked at the video footage and said it was a remarkable encounter. She explained that the shark was a sub-adult female, and her behaviour, typical of the species, was inquisitive – she didn’t seem aggressive at all.

Humans do not form part of a shark’s natural diet but they will investigate if they see a human splashing in the water – which can lead to an accidental attack. It’s best to avoid swimming in dirty water, near river mouths, near fisheries outlets, and at dawn and dusk.

Southern African great white sharks migrate along the coast up to northern KZN and Mozambique in the summer, as evidenced by satellite and acoustic tagging data. The sharks then follow the coast back down south, returning to the Cape shores in time for autumn and winter where they prey on Cape fur seals. They can tolerate a wide range of water temperatures but typically inhabit thermal ranges from 11-25°C.

The Tugela Banks and Mozambique Channel are historically rich in game fish and other shark and ray species in the summer, so for the majority of great white sharks, the movement north is probably prey-driven. It’s also possible that larger mature females head northwards into the Indian Ocean for breeding as warmer waters may facilitate the growth rate of their embryonic young.

As great white sharks age, their behaviour, movements and diet change. Similar to other migratory predators, their movements are complex and can often be difficult to interpret using tracking data alone, however we see similar patterns of movement behaviour in great white sharks of the same age and sex.

Great – and not so great – facts

South Africa was the first country in the world to protect great white sharks in 1991. They are listed as vulnerable on IUCN’s Red List and trade of their body parts is illegal as they are a Cites 2 listed species.

Shark nets and drumlines set up for bather safety are designed to trap sharks and will ultimately kill them if they’re not released quickly. The gillnets entangle and kill many other marine species including turtles, dolphins and whales. These measures are strongly debated and opposed by many.

Do this

For snorkelling and freediving trips to Aliwal Shoal, contact Cassie Weinberg at Wetu Safaris 076 590 0253, wetusafaris.co.za

For freediving courses in KZN, contact Freediving South Africa at 071 613 1953, freedivingsouthafrica.com

In Cape Town, contact Cape Town Freediving on 072 879 0772, capetownfreediving.com

Help protect

Ask at your local beach for authorities to change from shark nets and drumlines to shark spotters and other less harmful devices to deter sharks. There are many online campaigns and organisations lobbying for better protective measures for our oceans, including better enforcement of laws on sea and fisheries regulations. Find out more or donate to the following non-profits that conduct conservation work on sharks in SA:

– Shark Life (sharklife.co.za)

– Shark Spotters (sharkspotters.org.za)

– South African Shark Conservancy (sharkconservancy.org)

– Dyer Island Conservation Trust (dict.org.za)

– Ocean Research (oceans-research.com)

– Wild Oceans (wildtrust.co.za/wildoceans).