I remember Brian from varsity days – we completed our BSc Honours in ecology together at Stellenbosch University. He joined our class after having completed his undergraduate at the Nelson Mandela University and very quickly became known for two very specific skills: knowing the scientific name of every South African plant in the book (by heart), and sokkie-sokkie.

Brian has since progressed in both these areas of expertise, taking his nimble dance moves to compete at the Intervarsity Latin and Ballroom Dance competition, and bumping his academic career to up to a PhD at the University of Cape Town.

Brian du Preez is a PhD candidate at the University of Cape Town. He featured on RSG to chat about his latest plant rediscovery: P. cataracta. Image by: Brian du Preez

He’s also become reputed, this time beyond the classroom, for describing previously unknown plant species, and rediscovering long lost ones as well.

The budding taxonomist has rediscovered two presumed extinct species, Polhillia ignota and Aspalathus cordicarpa, last seen in 1928 and the 1950s respectively, and collected a new species of Aspalathus growing on the sand dunes of the banks of the Riet River in the Swartuggens Mountains north of Ceres.

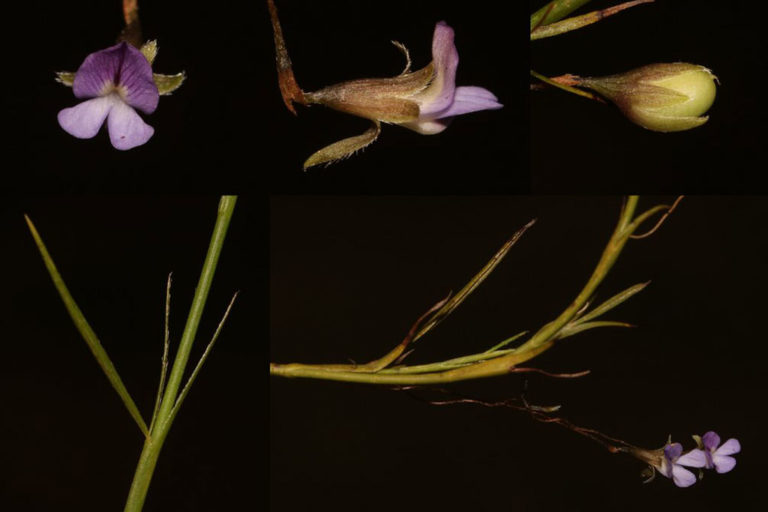

More recently, Brian rediscovered Psoralea cataracta (the fountain bush) which is one of the first recorded plant species to have been lost to forestry and agriculture in the Western Cape. Until now, P. cataracta was only known from a single specimen collected from ‘Tulbagh waterfall’ in 1804, and in 2008, was officially declared extinct.

But these incredible discoveries and rediscoveries might be for nothing as many areas where these rare and endangered species thrive are under threat of orchard expansion, meaning that the species may well become extinct after all.

I managed to track down Brian to ask him a few questions about his pursuit to preserve a very rare and very threatened floral kingdom.

Psoralea cataracta was last seen over 200 years ago. Image: Brian du Preez

You’ve recently taken front stage of the floral kingdom with your rediscovery of P. cataracta. How did you stumble upon this serendipitous discovery?

I came across them completely by accident while doing fieldwork for my PhD.

I was walking along a jeep track on a private farm on my way to the top of the mountain when I spotted them growing low to the ground right next to the track. The flowers were tiny, but because there was not much else flowering, they stood out.

You’ve chosen to revise the Indigofera genus as your PhD study. Can you elaborate on why you’ve chosen this genus specifically?

Indigofera is the second largest genus in the legume family within the Greater Cape Floristic Region (GCFR) and has not yet been fully revised.

Dr Brian Schrire, previously based at Royal Botanic KEW gardens, but recently retired, is the global Indigofera expert and worked for many years on the taxonomy of SA Indigofera, but retired before he could finish. So while he is still around to offer his knowledge and guidance, it is a good opportunity to fully revise the GCFR species from the platform that he has laid.

There are also at least 30 new species within this genus that still need to be described. And that’s just in the GCFR!

What is the significance of Indigofera? Why is it an important genus to you?

The problem with Indigofera is the large number of undescribed species. Without being properly described, they cannot be formally protected (and given a red list status) without being officially described in a published, peer-reviewed scientific journal.

Many of these new species are rare and threatened, and it is critical that these are described if we want to protect them.

What kind of agricultural development and expansion has contributed towards the loss of plant species from the GCFR specifically?

As a result of human impacts on natural areas, as well as, the spread of invasive alien plants and illegal harvesting of plants for the horticultural and medicinal trade, 2553 plant species are currently threatened with extinction in South Africa

Agriculture is one of the largest industries in the GCFR with a variety of crops being produced, from grains, citrus, meat and even rooibos tea made from the indigenous and naturally (not domestic) endangered Aspalathus linearis bush. This is a prime example where a plant species is being driven to extinction in the wild due to the ploughing of natural vegetation to plant domesticated crops. Most of the crop agriculture in the region has taken place in Renosterveld habitat, resulting in an over 90% loss of this vegetation type – several extinctions, and even more species clinging to survive on a thread.

The forestry industry has also played a major role in species loss within the GCFR. Not only have plantations been planted where they should not be allowed, but forestry companies also haven’t controlled escapee tree resulting in many of our mountains being infested with pine, wattle and Hakea species. The decline of Aspalathus cordicarpa, another species listed as extinct until we rediscovered it in 2016, was directly linked to forestry activity in the Riversdale area. The sooner we get rid of alien invasive species from our natural areas, including areas that can be rehabilitated to restore Critically Endangered vegetation such as at Tokai Park, the better.

We can also not see past urban expansion, which has led to many species extinctions, particularly in Cape Town and Stellenbosch.

The lesson to be learnt is that we cannot afford to destroy any more virgin land, and that all future development for urban or agriculture should only take place on disturbed or destroyed land.

There has been a lot of emphasis on diet recently as a means of reducing our global footprint. Will a diet change help conserve these silent extinctions?

It is unlikely that diet changes will lead to an improvement of the situation, most of the land surface that can be transformed for agriculture has already been transformed. The only way to prevent further habitat loss is to either improve agricultural practices to increase yield from the space already used, or curb population growth so that there is not a need to further transform natural habitats for urban or agricultural developments.

What else can us ‘average-Joes’ do to contribute towards the conservation of plant species?

Pine plantations, such as Tokai, are extremely unfriendly to the environment. Not only do they use as much as 40-50 litres of water per tree per day, but are a dangerous fire hazard and exclude indigenous biodiversity.

That’s a difficult question as the public can’t be directly involved in the conservation of many of our threatened species. But the best thing that citizens can do is be aware of the dangers that face our indigenous flora, and to look to live as sustainably as possible for the good of the entire planet.

1. Don’t support developments in ecologically sensitive areas, or areas where natural vegetation will be destroyed for new developments.

2. Join lobby groups and campaign for the protection of natural areas, and campaign against those wanting to destroy our natural environment.

3. If you are keen to get your hands a little dirty, join your local ‘Friends Of…’ group which will usually organize local activities such as alien tree hacks.

4. Pay better attention to what you read in the media, like fake news regarding the benefits of alien trees. There is simply no justification for keeping alien trees in the landscape when there is opportunity to preserve or restore our remaining fragments of undeveloped land

Someone told me recently that you cannot conserve something unless you love and appreciate it. Where, in your opinion, are the best places to travel within the Western Cape in order to appreciate the province’s floral diversity?

Unbounded, wild flowers spill over into towns, along highways and through fields in Namaqualand. Image: Getty Images.

There are many places to see at different times of the year, it all depends on what you want to see. Obvious candidate destinations are: Namaqualand for succulent plants and daisies during August and September, and Table Mountain and Cape Point for the beautiful fynbos and all of our botanical gardens for their incredible indigenous gardens.

I also encourage people to go off the beaten track and explore lesser-known areas, not necessarily the most isolated or dangerous mountains to climb, but there are trails and tracks covering many mountains in the region. The Overberg Renosterveld Reserve is one such gem. Lying in between a mass of wheat and canola fields, this small reserve is home to several newly described plant species and some spectacular flowers.

Contrary to widespread belief that fire destroys biodiversity, fire is an essential ecological process in the fynbos biome and the first few years after fire produces the best flowers. The first spring and summer after fire is when you see the best displays of orchids and various bulbs such as Gladiolus, Watsonia and Moraea species. The next few years are dominated by short-lived shrubs such as various colourful legumes, daisies and restios. If you are a fan of beautiful flowering Proteaceae, visit mature fynbos, but for the best fynbos has to offer, keep an eye on which mountains have recently burnt.

What species should these tourists look out for? Can you recommend any tools they should take on their travels?

Species diversity varies greatly in the region, with the assemblage of species between different mountains varying significantly. Anyone walking in the field should be attentive to anything in flower, whether big or small. Some species look rather cryptic from a distance, so you have to put your face against the flower to see its true beauty.

Be sure to carry your camera or cell phone around and take lots of photos. There are many field guides available as books or PDF’s, so get one that covers your local flora, page through it and start learning a few plants at a time.

Alternatively, you can take photos of plants in the field and upload to a citizen science platform such as iNaturalist, using the website or the free phone app available on both Android and Apple. This way, experts can identify the plants you have photographed, and you can even interact with them!

When is the best time to travel if you want to go flower spotting?

Late winter to early summer is generally the best period of time to see flowers in the GCFR, but there is always something flowering in the field! Most of our Amaryllid lilies flower March and April, so make sure you are in the field to see them too.

Have you ever sokkie’d amongst the flowers?

Brian was known for both his flower knowledge and his slick moves on the dance floor. Image by: Brian du Preez

No, but that sounds like a lovely idea!

Do you have any plans beyond this PhD?

No plans for certain yet, but I am keen to continue working on the taxonomy of GCFR legumes in some capacity, and of course spending as much time as possible in the field. My first priority now is to produce a good PhD and a comprehensive revision of Indigofera for the GCFR. If all goes well, we hope to publish a book on the Indigofera of the GCFR after completing the PhD.

Featured image: Brian du Preez