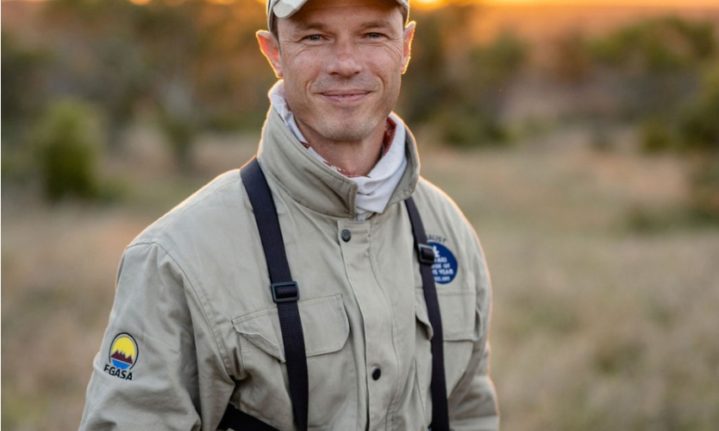

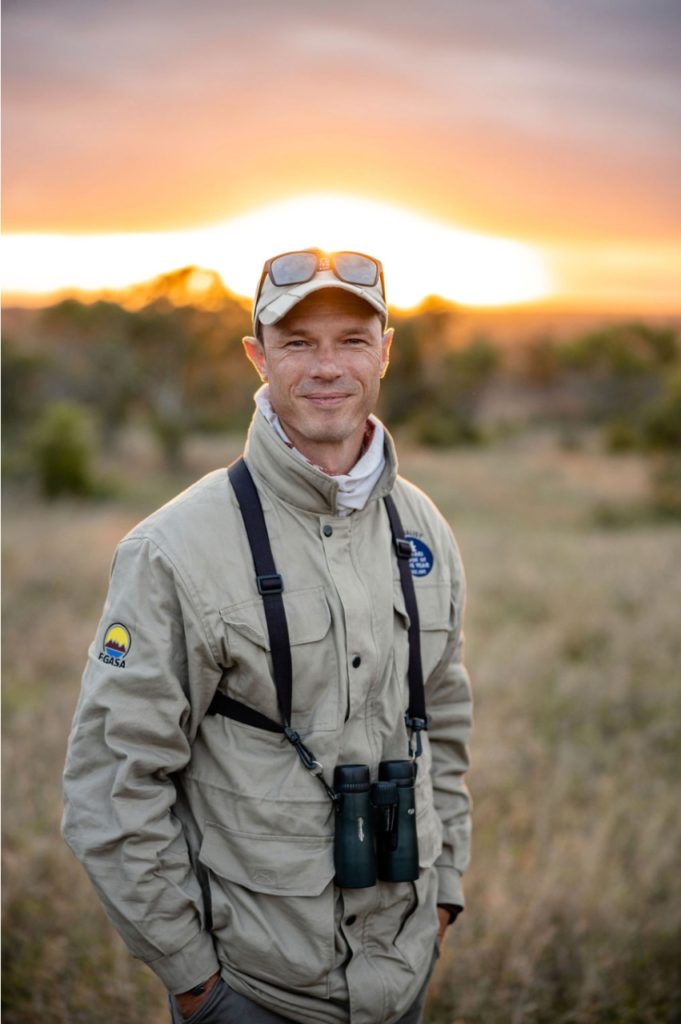

Named 2022’s Safari Guide of the Year, Cameron Pearce is just as happy spending a day twitching as he is out walking, behind a lens or sitting around a campfire. His motivation is simple: to be the best in the business, and to see as much of this magnificent continent as he can.

Interview by Lauren Dold

I might not be a rocket scientist, or somebody who’s very scientifically inclined or sales driven to make the most money, but I still want to be the best at what I do. Being a ranger is not just a holiday job, or something to do after university. I’m going to be doing this till I’m old and grey and too rickety to walk. That’s why I’ve taken the time to do all the additional courses, the extra qualifications. You can absolutely get a job with just a level one FGASA (Field Guides Association South Africa) qualification, but this is my career. And it’s a lifelong passion.

I started off working in the Sabi Sands, and then I worked at Tswalu in the Kalahari for three years. I’ve tried not to get too caught up in a bubble, but instead I’ve tried to see as much as I possibly can, to experience as many different environments as I can. Your exposure affects your style of guiding; the more you’ve experienced, the greater your understanding of how everything pieces together.

I’ve done a lot of field guide training over the years, and I learn from the students all the time. It’s so important to spend time with other guides. Even if you think you might not know as much as the next guy, use that time to ask questions. Spend time with people who are experts in their respective field, as many experts as you can, because no one can be an expert in everything.

One of my pet peeves in guiding is putting too much pressure on animals. In certain parts of Greater Kruger, guides drive too close to animals because they can, because the animals are habituated. They’ll park two metres away from a leopard.

I was guilty of that when I was younger. One day I was sitting with my best friend at a leopard sighting. The leopard had an impala carcass on the ground and her two little cubs were feeding on it. She was literally two metres away from the passenger door.

‘This is epic,’ I thought. ‘You don’t typically get to see leopard cubs this close, in the open. I hope he realises how lucky he is.’ My friend turned to me and said: ‘Your leopards here are kind of tame, right?’ And I had this devastating realisation that I’d stolen that leopard’s mystique from him. Just because you can get within two metres, doesn’t mean that you have to.

Obviously you should improve your position photographically for your guests – you don’t want to have too many branches in the way – but often it’s better to be

a bit further away for photographs. So I think that I’d like to see guides having a little bit more sensitivity, building up a sighting from a distance instead of just zooming right in there.

Then of course there are the corny jokes – it would be great to hear fewer of them. Unfortunately, it becomes a style of guiding. You can forgive the odd joke here and there but when you’ve heard about the flying banana (yellow-billed hornbill) and the McDonald’s of the bush (impala) a hundred times, it becomes tiresome. It’s important to know who your guests are, and to adapt your guiding accordingly.

At Tswalu late one afternoon, in an area known for aardvark, aardwolf and pangolin sightings, I saw something I’ll never see again. We’d already seen three or four aardvark that afternoon. Just as the sun was about to set, we saw another one, and I positioned us to approach on foot. They’re a little bit like rhinos in that they have very poor eyesight, but very good hearing and sense of smell. So if you use the wind the same way that you would use it when approaching rhinos, often you can get within several metres of them on foot. We were about to do that when we noticed a second aardvark, on course to collide with the first. So we hung back a little bit, and sure enough they bumped right into each other.

They both reared up on their hind legs and started to pat at each other’s faces and chests.

It was bizarre. We weren’t sure whether it was going to be an aggressive interaction, but it seemed to be more on the friendly side, a kind of greeting. I’m still stunned I managed to capture that.

Once, we came across a leopard that had taken its kill up into a tree, stashed it and gone to fetch its cub. While it was away, there were two hyenas that had been lying under the tree; one of them started sniffing around, looking up at the tree, calculating. It was a jacket plum, and the hyena figured it could shimmy its way up.

The hyena got about 5m up, grabbed this wildebeest and fell back down. The leopardess returned with its cub, but couldn’t believe its kill was gone, knowing that hyenas don’t climb trees. So she became very aggressive towards us; she genuinely thought we’d stolen her kill.

The future of safaris is specialisation. We’re starting to see the end of this formula of a morning game drive, breakfast, a half-hearted bushwalk and an evening drive with a bit of photography. Those general, gentle bushwalks are going to die away. Specialised trips are becoming more popular. If you’re looking to walk, you’ll book a trail, photographers will seek out specialist photographers, and birders will opt for birding safaris instead of going to a lodge that does a little bit of everything.

Pictures: Kyle and Nicolene Cresswell/ Armadillo Media

Follow us on social media for more travel news, inspiration, and guides. You can also tag us to be featured.

TikTok | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter

ALSO READ: Unsung heroes: Meet the power team behind African Wildlife Vets