I’ve just landed on the Greek isle of Ikaria, unknown to me nine months ago. The airport is a single room, with a lone, unmoving baggage belt.

As the other 30 passengers disperse, I notice a giant sculpture, a carved tree full of faces, animal and human. Fairies already working their magic.

I don’t see my guide or bag, so I approach a woman in a small cubicle, the ‘information desk’. Yassou, I say, smiling, hopeful. Is that where the luggage comes out?

I sense we’re on ‘Ikarian time,’ and not to stress. Ah, the woman behind the counter says, studying me, intuiting. You are the sort of person who will love it here.

Within minutes, after my pre-arranged guide Lina fetches me and drives the infinite curves of the rough island roads, I am that person.

Inspired by the Netflix doccie released last September, ‘Live to 100,’ I’ve come to experience ‘the Blue Zone lifestyle,’ to learn firsthand Ikaria’s secrets – why it’s one of the world’s five Blue Zones where people live long, because they live well.

‘People say the longevity is due to the exercise, the healthy diet,’ Lina says, herself an avid hiker and hiking guide. ‘But it’s more than that. People here are connected, you never feel alone. They are independent. They have a sense of freedom. And they are very good at having fun.’

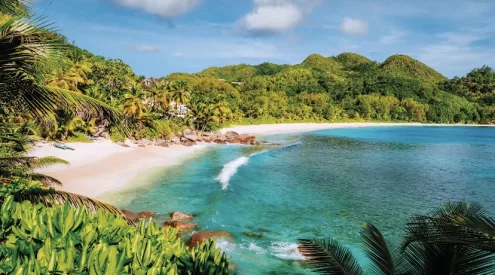

Mountainous, wild Ikaria, 30 miles off the coast of Turkey in the Eastern Aegean, has a tumultuous past, besieged by pirates, occupied by the Turks until 1922, a centre of resistance; no wonder its people are strong, maybe a little wild themselves.

It’s a rich past: the birthplace of Dionysus, the god of wine, the island’s known for its natural wines produced for centuries. Its Pramnion wine was mentioned in the works of Homer. Its name comes from Icarus – whose waxed wings melted when he flew too close to the sun, fell into the sea, and was buried on the island.

More recently, though, longevity has become Ikaria’s touchstone. Thirty percent of its 8,000 residents live into their 90s, with many hitting 100 and beyond.

Maybe genes play a part, but it also comes down to how Ikarians have been living for generations: close to nature; sustainably and largely self-sufficient; nurtured by a largely plant-based diet dominated by horta, more than 80 varieties of wild greens, plus herbs, olive oil, vegetables, legumes, and of course a regular amount of that natural wine. Plus, as Lina and later other Ikarians tell me, living in community, caring for each other.

Not far from the airport, Lina stops the car, gets out, gathers herbs on the roadside.

Come, she says, and holds bunches of aromatic herbs under my nose: thyme, rosemary, sage; herbs smell stronger here. This one is anti-inflammatory, that one’s an anti-oxidant, another minimises dementia. Reminiscent of San Bushmen’s medicinal use of the veld.

We drive on, almost the only ones on the road. Lina’s customised a rambling island tour, winding up at a panagyri, traditional festival, high up in the mountains this afternoon.

I stare at the wide, deep blue sea, and listen to her travelogue: how you can see at least 10 other islands from Ikaria; how few fishermen there are here, people prefer to eat goat; how you call your grandmother to say a prayer if you suspect someone’s given you the ‘evil eye,’ out of jealousy causing you harm.

‘We believe in it,’ she says. ‘Even the Church has a prayer for this. When the researchers came here to study longevity, many of the old people ran away from them and hid. They thought they were bringing the evil eye.’

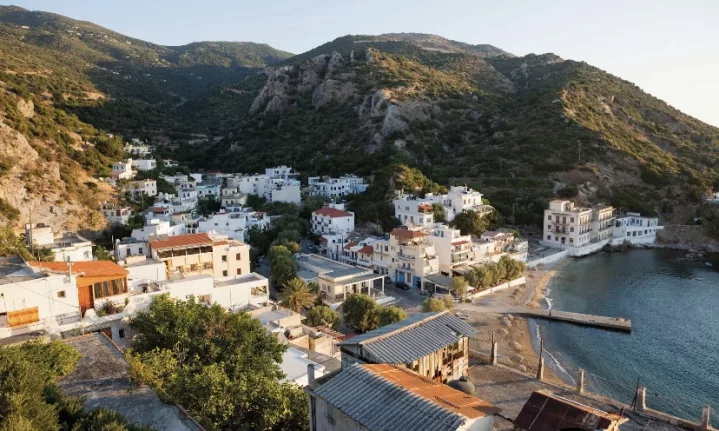

Soon we reach Therma, a small village with hot springs spilling into the sea, where hydrotherapy’s been practiced since the 4th century BC.

ALSO READ: Why Greece should be on your bucket list

No one’s around, we think, so start changing into our bathing suits in the street, using the car as a shield, slightly. But then the car behind us comes alive, revs, drives off – and back again, for another look.

We wait till he/she disappears and, in our bathers, walk down the uneven steps and plunge into the green, hot/cold water, swimming into the warmest spots. Divine.

By the time, hours later, we reach Raches – a collection of five 500-metre high villages in the island’s west – I’m woozy from all the hairpin turns.

We slow down and pass vignettes frozen in time: miniscule town squares, men gathering at the kafeneion, children playing in the streets, but mostly empty – few cars, few people.

‘People here come out, come alive at night,’ Lina says. ‘From the 15th century, they lived like this. Staying inside all day, trying to deceive the pirates.’

At last we reach our destination, high on a rocky plateau, littered with cars and people walking toward energetic bouzouki music. It’s a panagyri honouring Agios (Saint) Isidoros, sponsored by the tiny local church seemingly in the middle of nowhere.

Hundreds of Greeks and far fewer tourists are dancing madly, drinking copious amounts of red wine, and eating piles of goat meat and various vegetables. We forego the goat, drink far too much wine, and soon are circling around with the hand-holding crowd, faster and faster to the most popular local dance, the sirto. Lina seems to know everyone. I’m grateful to still ably walk back to our car three hours later.

The next two days, happily settled in an old cottage in Armenistis, Ikaria’s tourist hub, I drift along its main road, meeting more cats than people.

Delighted to hear the bells of the blue-roofed church nearby, to shop at the one supermarket, to swim in the crystalline waters at the local pebble beach. A supreme calm takes over; I tell my friends I’m staying here forever, but of course I’m not.

To know more about the Blue Zone lifestyle, I go to where it’s practiced daily, and deeply. Run by Yorgos (George) Karimalis and wife Eleni, Karimalis Winery (ikarianwine.gr) in Pigi, a village southwest of Evdilos, has become world-famous for its natural wines, produced as they have been for 3,500 years, and for Eleni’s mostly plant-based wizardry in the kitchen.

They’re writing a book together, hopefully released next year, a combo food and lifestyle book to further spread the Blue Zone gospel.

‘There are three things that define longevity,’ says Yorgos, winemaker and life coach who 42 years ago, at age 24, inherited the 500 year-old winery from his grandfather. ‘Nutrition. Habits. Movement.’ He pauses for a moment; a writer and photographer from Lonely Planet, also seated at the supper table, hang on his words.

‘But longevity also means keeping the generations together,’ he adds in an ardent, raspy voice. ‘There’s only one old-age home on the island, for people with totally no family.’ He voraciously tucks into the head of a long, slim fish we’ve dined on. ‘People who live long don’t eat alone…they share.’

Eleni is equally passionate. ‘I grew up in this lifestyle,’ she says the next morning, prepping vegetables for soufiko, loosely an Ikarian ratatouille, in the winery’s vast kitchen. She speaks lovingly of food and family, of the herbs, greens, goats and chickens on hand, of her grandmother who died at age 100, of her four children. Over two days I witness her culinary magic, especially in her four-hour cooking class just before I depart.

We four acolytes don ‘Ikarian Cooking School’ aprons and start the apprenticeship. On the menu today: fava, a garlicky spread like hummus but made from yellow split peas; soufiko, to be served with Eleni’s homemade pasta; little phyllo pastry pies stuffed with wild greens; salad of greens, tomatoes, olives, herbs and sesame seeds.

Mostly plant-based dishes; they eat fish and meat just once a week here. Sublimely healthy, tasty, and made with care, with intention. Food is never fried; olive oil is mostly added at the end, to retain its benefits; veggies are cut precisely according to cooking time; meat is always cooked on its own. Herbs, mostly fresh, are used abundantly.

We wash and chop and knead, following Eleni’s inspiring example. As one of her staff says later, explaining the Greek word meraki: ‘It’s when you put a part of your soul into what you do. Eleni exemplifies this.’

Most fun, and most challenging, is making phyllo dough for the mini-pies. With long, thin rolling sticks we roll and roll, hands moving out to the edges then back to the centre again, rotating the dough, then rolling the stick quickly closer and flinging it away. Ultimately, each sheet hanging, almost transparent, like a roundish flag.

Finally finished, lunch is eaten with great relish; we’re proud of ourselves. We celebrate with an off-dry Rosé, honey-touched 2022 Akissare, from the vineyard.

I don’t want to go. I want to hear more about the nun, once captured by pirates from Lesbos, sanctified and buried at the tiny local monastery. To drink more of the unadulterated Karimalis wine. To stare longer out the window of my little stone room, out over the vines to the sea.

As I prepare to go, I wonder if the younger generation subscribes to the ‘Blue Zone lifestyle’. I ask Giana, the winery’s 32-year-old restaurant manager for the summer season, who’s spent much of her adult life in Chicago.

‘One of the best Blue Zone aspects,’ she says, ‘is the feeling that we’re all in this together, like the feeling at a panagyri. No one gets left behind. As a girl I had a taste of that community, before the Internet. We played outside. We all knew each other. We want to get back to that.’

This article was written by Melissa Siebert for Getaway’s October 2024 print edition. Find us on shelves for more!

(Pictures: Courtesy Images)

Follow us on social media for more travel news, inspiration, and guides. You can also tag us to be featured.

TikTok | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter

ALSO READ: ‘I Speak for the Sea’: SA dive master committed to conservation