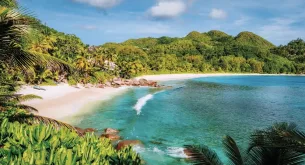

An adventure route connects the magnificent waterfalls of the Wild Coast and immerses travellers in vibrant culture and wilderness.

Angel Falls, near the Magwa Tea Estate, is just off the road to Mbotyi.

Some afternoons linger with you long, long after the sun has set. They mightn’t be marked by a life-changing event, but there’s something about them your memory refuses to let go of, and it’s to that afternoon, or rather, to a place and a moment in an afternoon, that your mind often returns.

One such time and place that refuses to leave me is a sunny half-hour on a rainy Wild Coast day and a large slab of sandstone on the Mphahlane River. It’s probably a river you’ve never heard of – and that’s precisely what made this afternoon so special. While rain clouds dissolved into patches of blue sky and water slipped over a gentle gradient into an idyllic pool, I settled down on a rock – its mild warmth seeping into my skin – and marvelled: ‘This place is exquisite … and nobody else in the world knows it exists.’

That’s not entirely true – for generations, the children of nearby Sigidi village have played here. But as we approached the river, it was barely visible, tucked as it is into an unexpected crack in the grassland, and that sense of untouched isolation was captivating.

Ground hornbills are considered callers of the rain.

Beside that river, I witnessed Earth in action. The slab I was lying on sloped down into a wall of sedimentary rock that was undercut by the constant flow of water; my fingers traced cracked layers of Msikaba sandstone, its sediments laid down beneath the ocean some 400 million years ago. Huddles of Strelitzia nicolai had sent their roots between the rocks above me, and above them, two crowned cranes glided inland.

Far off – I was quite certain – rumbled the low, thunderous call of a southern ground hornbill. ‘The rain bird,’ explained Tutani Mpunga, a senior guide who’s lived his life on this land and knows its flora and fauna intimately. ‘Here, people say that if you want it to rain, you must submerge a ground hornbill – or just its feather – in a river. But you must always tie a string to it, so that once there’s been enough rain, you can pull it out of the water, to make the rain stop.’

That afternoon was the first on a week-long trip through Pondoland – northern Wild Coast – during which we had one specific mission: to chase waterfalls. Starting at the Mtamvuna River near Port Edward, we headed further south each day; our Ford Ranger tackling the network of muddy roads and, when the weather allowed (for there must have been a hornbill feather in a river somewhere), our feet carrying us across wild coastal hills and connecting one waterfall with another, and another. Magnificent waterfalls, it turns out, are something the Wild Coast has in abundance. Particularly during a week of near-constant rain.

The cascade we ‘found’ along the Mphahlane River – where water slid down a flat rock into a pool fringed with an explosion of palmiet shrubs – was beyond pretty, but it was by no means the most spectacular, for the waterfalls of the Wild Coast are utterly astounding.

Waterfall Bluff

There is well-known Waterfall Bluff, where the Mlambomkulu River drops directly into the Indian Ocean. Near Xolobeni, the Mnyameni River carved a mighty amphitheatre before it found a weak spot where, over millennia, the water has managed to cut a short but near-vertical gorge into the cliff-line. Msikaba sandstone, the predominant rock type along the Wild Coast, is resistant to erosion, which is why steep-sided gorges and ravines abound.

About 23km northeast of Lusikisiki, the Ntentule River plummets over a broad bluff. Sanral surveyors working nearby on the 850m-long, R165-billion Msikaba Mega Bridge (which is part of the controversial N2 Wild Coast Road) calculated that this little-known waterfall is 175.4m high – the second-highest in the country after Tugela Falls (947m). Along the narrow Mkozi River, a few kilometres upstream from Mbotyi, the astonishing Fraser Falls drops three dramatic steps between forested cliffs; and not too far away at the almost-hidden Magwa Falls, the Mzizangwa River plunges 142m over a sharp, broad ledge and then continues its journey at 90 degrees to its higher course.

MaNoxolile and her family are the gracious hosts of a homestay in Cutwini village.

While the waterfalls themselves are remarkable, I loved meandering between them even more. The week we spent with Tutani, learning about Mpondo culture and traditions, as well as the plants and their uses – umkhulu (forest mahogany) for lower back pain; isiQalaba (common sugarbush) to heal broken bones; inqubebe (large blue scilla) for soap – helped me to connect deeper with the area I was quickly falling for.

In that week, I didn’t just visit – I truly belonged. We stayed at homestay huts and were welcomed with open arms – quite literally – by our host families, and we parted as friends. We also left with our bellies bulging from feasts of delicious homemade bread and meals prepared from ingredients grown in our hosts’ gardens.

We journeyed with our heads full of stories. Some flowers, Tutani explained, can be used as a calendar: a coral tree in bloom means it’s time to plant sorghum and mealies. In Msikaba, over tea and cake baked by MaNtshangase, MaLudude told us how the women of her village work together to ensure profits from the village homestays are shared evenly.

The best way to explore this series of pretty waterfalls at Hidden Valley is with a guide.

In Rhole, Mr Nkunde described how he’d burn a handful of dry ibhulu leaves (senecio rhyncholaenus) outside his homestead to keep lightning away. In MaNoxolile’s kitchen at Cutwini, we shared a beer with a sangoma who explained the importance of waterfalls to the Mpondo people. Water collected at a waterfall is used for isikhafulo – medicine to ward off evil spirits – and can also be used to help someone who is seeking a lover. The messages she sent, the sangoma said, would be conveyed much faster if she used water collected from a waterfall, because of the speed at which it flows.

Just as some afternoons will linger with you long after the sun has set, and just as a sun-baked rock can seep warmth into your limbs, so a place can steep into your being and render you changed, somehow. Perspectives shift and you become more passionate; compassionate. Rested. Invigorated. Connected. It’s humbling, the things you can catch when you set out to chase waterfalls.

This article was adapted from a version that appeared in our February 2022 magazine issue.

Orginally written and photographed by Narina Exelby.

Follow us on social media for more travel news, inspiration, and guides. You can also tag us to be featured.

TikTok | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter

ALSO READ: The quiz that all adventurers need when planning their next holiday