Every year, the team at the Two Oceans Aquarium saves dozens of sea turtles from certain death. This is the story of how one of them returned to the ocean …

A rehabilitated loggerhead turtle returns to the deep-water currents of Cape Point.

Words & photos: Jacques Marais

I first met Annie when I drove her to the ‘human hospital’. Let me explain: the Annie in question is a loggerhead turtle, and she needed a check-up because she had been swimming around her tank at the Two Oceans Aquarium in Cape Town’s V&A Waterfront with her bottom bobbing skywards at a 45-degree angle.

Fortunately, the series of CT scans and ultrasounds at Tygerberg Hospital showed that upside-down Annie was in good health: her buoyant derrière was due to some excess gassiness (which earned her the nickname ‘Bubble-Butt’).

Annie – like hundreds of other sea turtles – ended up at the Two Oceans Aquarium after she was rescued. This often happens when the turtles are stranded in icy waters outside the Mozambique current. They suffer from hypothermia and, eventually, dehydration. It is often members of the public who rescue the stranded turtles when storm winds and swell wash them on to beaches, usually between March and July.

Mother Nature is not always to blame, though. Injuries are often related to boat strikes, plastics ingestion or entanglement in fish nets – which is what happened to Annie. She was stuck in a fishing net but was fortunately rescued by the National Sea Rescue Institute (NSRI). Despite her extremely weakened state, the rescuers managed to get her to the aquarium, where she settled in for two years of rehabilitation with the Two Oceans Aquarium Education Foundation.

The Two Oceans Aquarium and NSRI vessels leaving Hout Bay harbour.

These turtle heroes fed Annie and gave her inter-coelomic fluids until – after more than five anxious months – she started to eat on her own again. The ‘strong, feisty and very healthy’ loggerhead I met weighed in at a robust 150kg and was a darling of the crowds at the I&J Ocean Exhibit tanks at the aquarium.

Annie is undoubtedly a survivor. Dedicated care by the incredible ‘Turtle Rehab Team’ had seen her gain enough weight (and attitude!) to take the next step. This is always a bittersweet moment for these ocean warriors – especially after years of close contact while rehabilitating these amazing marine creatures – but ultimately, turtles must return to the Big Blue.

The only way to do this is an open-ocean release into the deep, warm-water currents off Cape Point, where Annie eventually said a final goodbye to her humans. Following a barrage of medical tests and preparations by the team, Annie was fitted with a tracker, allowing the foundation to follow her on her ocean travels, while also capturing important scientific data to improve their knowledge of the species.

For one last time, Annie (with a batch of juvenile turtles, a green and two leatherback adults) faced the traffic as the Isuzu ‘Turtle Taxi’ ferried them from the V&A Waterfront to Hout Bay Harbour. Here, they were loaded on to the NSRI and Hooked on Fishing boats to navigate the surging swell en route to Cape Point.

Annie being readied for her journey into the Atlantic Ocean after nearly two years with ‘her humans’.

We set off about an hour after sunrise, accompanied by assorted aquarists, vets, a marine biologist, the boat crew and some media people looking green around the gills. It was rough going against a stiff breeze, making for a bumpy cruise of nearly three hours.

We needed to get beyond the Peninsula’s coastal waters – where the mercury generally hangs around 10°C to 15°C – and to do so, we had to find the warm Mozambique current. The temperature did not rise much during the first 20 sea miles, but suddenly the instrument console started ticking over: 10.1, 10.2, 10.4, 11.8, 13.6, 17.9…

Just like that, we were out of the icy Cape waters and moored in comparatively tropical conditions. All around, the Atlantic steepened like a molten-blue lake, with 400m of crystal-clear water beneath us. It is in these depths that turtles live and play, while we humans furtively visit, often like bandits poised to pillage the marine bounty or pollute the ocean.

The people on the boat with me were different. They were here to balance the scales ever so slightly, and to give back to Mother Nature. I sat quietly to one side absorbing the moment, then donned my wetsuit and fins to slip into the aquatic embrace.

A ‘Turtle Hero’ snaps a last image before one of the loggerhead juveniles disappears into the Big Blue.

Gannets, petrels and skuas swooped low across the surface; open-ocean swells the size of houses rolled in from Antarctica; a distant, hazy wisp of land rose above the waterline every now and then to the northeast … when you finally peer down into the water, it is so profoundly deep and hauntingly beautiful that it takes your breath away. Literally.

When Annie eventually came out of the hold space for the first time, you could almost see every atom in her turtle body begin to vibrate with an ancient, primal force. The sea was calling her and, come what may, she needed to dive … downwards and deep, to where indigo currents swirl along the unfathomable ocean floor.

The volunteers holding her bulk could barely contain her as she strained to cross the bulwark of the boat, flippers scraping furiously at the air, neck extended towards her aqua paradise. I realised I had literally a few seconds to shoot before she disappeared. And in the stillness of that moment, I could sense the roil of bittersweet emotion from her humans as they realised this would ultimately be a forever goodbye.

Before her fins touched the surface, Annie was already swimming. She bobbed for a milli-second – maybe because of that Bubble-Butt – almost as if to say ‘Goodbye humans, and thanks for all the fish. The plastic… not so much’. Then, with a final splash of her flippers, she dipped into the other side.

Volunteers and Two Oceans Aquarium crew get ready to release Luis.

I watched her through the camera as she receded into the cobalt gloom, then followed her for a few metres before my oxygen craving got the better of me. And then it was just us humans, bobbing in the immensity of the open ocean way beyond Cape Point, surrounded by a few box jellyfish and those unseen denizens of the deep.

Everything was eerily quiet as I drifted on the tide and – I would like to think – everyone’s thoughts were deep beneath the surface of this great ocean, wondering what awaited Annie, and where her incredible journey would take her. Then I thought of great white sharks, and surreptitiously finned closer to the boat. Just in case …

Do mutant turtles exist?

Cowabunga!

In the movies, Donatello, Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael fight crime from their den in the New York City sewers. It is a stretch but there is some kernel of truth in their back story.

National Geographic reports that red-eared sliders (Trachemys scripta elegans), the most popular freshwater turtle in the American pet trade, is taking over waterways in the Big Apple, such as Morningside Pond. Native to the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico, they are bred on an industrial scale and are sold wholesale to pet retailers.

Red-eared sliders are consistently named one of the world’s hundred worst invasive species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature because when pet owners discover they need big tanks and expensive filtration systems, and can live for up to 50 years, they often dump them outside – where they are becoming a nuisance and are crowding out native species, creating harmful algal blooms in local waterways, and possibly exposing humans to salmonella.

Freshwater turtles are called terrapins in South Africa, and while red-eared sliders are sold through the internet into the pet trade in the country, it is illegal to do so. The Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment reports that it is an offence in terms of the Alien and Invasive Species Regulations to breed or sell the Trachemys species.

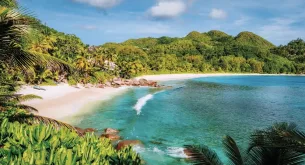

A turtle soaks up the sun on the surface before diving into the warm waters of the Mozambique current.

Get involved

You can be a part of this circle: the Two Oceans Aquarium Education Foundation is a registered non-profit and public benefit organisation, and it is your donations and voluntary assistance that will help the next batch of sea turtles. Visit aquariumfoundation.org.za now for information on the foundation’s impactful programmes.