With an estimated 48-60 caracals remaining in Cape Town, it is the Mother City’s largest remaining predator. These resilient felines have shown an impressive ability to adapt to urban environments, but recent studies reveal their relationship to peri-urban environments is turning toxic.

Bioaccumulation

Every living organism bioaccumulates organic and inorganic substances. According to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry ‘bioaccumulation is the build-up of a chemical in an organism due to direct uptake from the environmental matrix and uptake from food. Bioaccumulation only occurs when the uptake exceeds elimination.’

Bioaccumulation is usually taken up indirectly through the food chain and builds up the higher you are. Mercury is a well-known example of bioaccumulation amongst humans, which can lead to Minimata disease, a severe neurological condition caused after eating contaminated seafood.

Within urban environments, pollutants are frequently emitted into the surrounding atmosphere and poisons are often used to control certain ‘pest’ species such as rodents and insects. What remains vastly unexplored, however, is the bioaccumulation of these pollutants in the food chain, especially amongst animals like caracals.

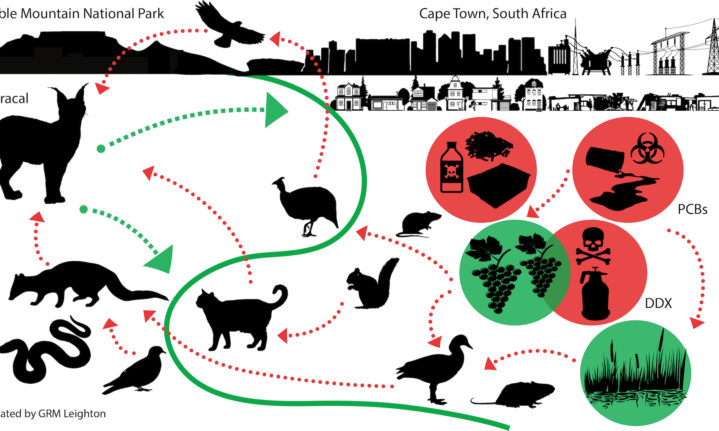

Dr Gabriella Leighton, along with other researchers from the Urban Caracal Project recently conducted the first investigation on the exposure of caracals to pollutants in an urban environment.

‘Poisoned chalice’

Picture: Luke Nelson

The altering of landscapes and urbanisation are considered some of the main contributing factors to the rise in infectious diseases among wildlife. There has never been an extensive study on the health of caracals in these modified landscapes until now.

According to the study, Cape Town is a potential ‘poisoned chalice’ for resident carnivores, attracted by the abundant prey associated with transformed landscapes which in turn exposed them to a cocktail of harmful chemicals.

The release of these pollutants can be attributed to industrial and household cleaning products but usually, it is the intentional use of pesticides and the use of illegal chemicals. Unfortunately, South Africa is the largest importer of pesticides in sub-Saharan Africa.

Many of these pesticides have a legacy that outlives their intended use and are still detected in the local environment at some of the highest concentrations globally. The potential spillover of these pollutants into natural areas adjacent to cities is likely to be high ‘with serious consequences for humans, livestock and biodiversity’.

Because of caracals place at the top of the food chain, they are a key indicator species, and their exposure can be indicative of the wider ecosystem.

Living on the edge

A caracal spotted in Simons Town. Picture: Yolande Oelson

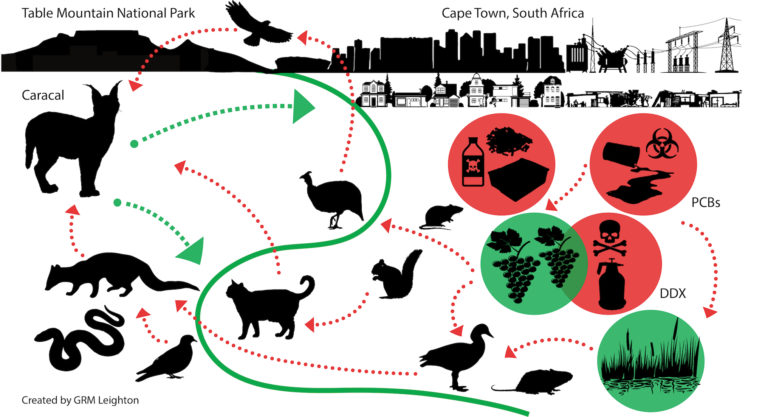

Caracals are attracted to the urban edge, where they supplement their diet with human-associated species such as rodents, which can expose them to harmful pollutants. To find out the levels and effects of contamination, Caracals were captured through standard trapping techniques and fitted with drop-off GPS collars. Blood samples were taken at every capture and recapture.

Additionally, caracal carcasses were also collected through the study area, where tissue samples were also taken. For the study, the age class, sex, weight, and measurements were recorded.

A caracal trapped as part of the study.

‘We explored the association between body condition and blood measures with concentrations of toxicants in caracal blood samples’ Leighton said. ‘While we did not find a link with body condition we did find that several measures of infection-fighting cells were increased in caracals with higher levels of toxicants.’

Caracals in specific forage areas, such as vineyards and wetlands recorded high levels of exposure, especially DDT. When asking Dr Leighton if agricultural areas are prime suspects, she mentioned that the traces of pesticides are difficult to determine.

‘The sources of these pollutants are tricky to pick apart because they last so long in ecosystems, therefore, it is sometimes difficult to tell whether the exposure we see is from the current or historical use of pesticides, such as DDT, on farms’, she states. ‘If the sources are contemporary, a way forward may be to instigate a national retrieval program for stockpiles of obsolete chemicals, which may still illegally be in use’.

Jasper, a caracal who roams Table Mountain was fitted with a traffic collar after the capture.

After taking blood samples, all of Cape Town’s caracals were found to have traces of exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) – a carcinogen often used in household and industrial equipment. What’s more, is that individuals who fed on human-associated prey were found to have higher levels of PCBs.

‘For PCBs specifically, we found there was an association between the density of electrical transformers and levels detected in caracals’ according to Leighton. ‘This association has also been found for Black harriers, an endangered raptor in the Western Cape.’ South Africa has committed to eliminating the use of PCBs by 2025.

‘To reduce further contamination, ESKOM and the City of Cape Town urgently need to update any electrical transformer units and substations that contain old, PCB-contaminated equipment. While removal plans are already in place… these need to be expedited to reduce leakage and ‘spillover’ into wildlife’.

Health implications on caracals

Although it’s difficult to pinpoint the exact effect on caracals due to the lack of research, Leighton believes that levels do not have to be high to be an issue. ‘These toxicants can have sublethal effects that accumulate over time,’ she argues. ‘Further, these organochlorines are not the only threats with which caracals contend.’

Even though the effects of pollutants cannot be directly attributed to caracal mortality, it does compromise their health.

‘On the Cape Peninsula, caracals are also exposed to rat poisons and novel blood pathogens. We are also currently analysing data we have on caracal exposure to heavy metals associated with urban areas, like lead, arsenic and mercury. Together, this cocktail of various environmental pollutants could work in concert to negatively impact wildlife health.’

While mentioning that there is no data to determine whether or not this is getting worse, ‘we do know that caracals around Cape Town face many novel threats, so reducing causes of mortality or ill-health where possible will be central to their persistence in this area.’

Is there hope for Cape Town’s caracals?

Picture: Anya Adendorff.

‘Caracals are a remarkably adaptable and resilient species,’ Leighton mentions. ‘They can persist and thrive in an impressive variety of habitats, and make use of any resources available to them.’ On the Cape Peninsula, however, populations are isolated thanks to urban sprawl and habitat fragmentation.

Threats of traffic, exposure to novel diseases and pollutants all negatively affect the species. ‘If we do not act to conserve the remaining individuals, the population here might become locally extinct. But there is hope if we do choose to act,’ Leighton says.

South Africa has committed to eliminating the use of PCBs by 2025 but ensuring the ecological integrity of their remaining habitat is crucial for the continued survival of the city’s caracals. However, their conservation will only be a success if we can reduce their main threats.

‘This will include traffic calming in known caracal road-crossing hotspots; education to reduce persecution of this natural predator; and efforts to reduce poison use and environmental cleanup of contaminated areas, such as wetlands and agricultural areas.’

The bioaccumulation documented suggests that apex predators, such as the Cape leopard and birds of prey will also be vulnerable to indirect exposure. Even though the caracal has proven to be resilient in adapting to life in the big city and the work by the Urban Caracal Project is garnishing public awareness, work needs to be done to ensure the survival of these species in Cape Town, where they are steadily becoming an icon.

Pictures: Supplied by The Urban Caracal Project

ALSO READ

Between the scales: why is there such a high demand for pangolins?