Himalayan Run & Trek is a 160-kilometre stage race in the Darjeeling District of India. With a backdrop of some of the world’s highest mountains, this adventure takes you along the border of Nepal where yaks, red pandas and wild horses roam free.

The view from Sherpa Lodge’s dining room in the mountain village of Rimbik, which looks towards Sikkim, a state in northeast India bordered by Bhutan, Tibet and Nepal. Image: Michelle Hardie.

My yearning to visit India began a long time ago. I was nine when I received my first ‘love letter’ from the young son of Indian shopkeepers in our village in Zimbabwe. Dilip’s dark eyes and slanty blue writing set my heart aflutter. In his family’s shop, I watched his mum unravelling rolls of fabric, the sound of its weight going ‘thud thud’ as it flopped along the wooden counter. She had a red dot on her forehead, wore a sari and had a glittering stone on the side of her nose. The memory of this exotic scene re-emerged 40 years later as I stood in a New Delhi shop observing a salesman plonk fabrics onto a counter.

I had arrived in the capital 10 days earlier and from there flew two hours east to the Darjeeling District for the Himalayan Run Trek (HRT). The event follows a 160-kilometre route threading through the Himalayan foothills and run over five days. Runners have dubbed it ‘the most spectacular race in the world’. But it’s open to walkers too – well, anyone really who is relatively fit (this includes enough power in your thigh muscles to use a squat toilet and a stomach strong enough not to pass out). I was part of the media contingent, and I happily joined the walkers.

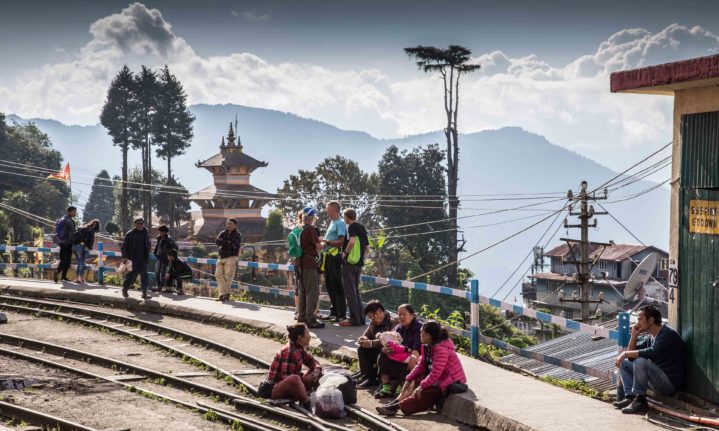

The picturesque setting of Darjeeling station. The famous Toy Train arrives and leaves from here on it’s 88-kilometre route to New Jalpaiguri station in Siliguri, the gateway to Nepal, Bhutan and Bangladesh. Image: Michelle Hardie.

The routes traverse mountains, jungles and forests, with sleepovers in small towns and villages. HRT has chosen the setting for good reason; the region has a cool climate, unpolluted air, vast tea plantations and magnificent views of the Himalaya (this is where the Indian and British colonial elite took their summers to avoid the scorching heat of the lowlands).

In total, we were a group of 28 runners and walkers – 12 Brits, nine Americans, three South Africans, three Indians and a German. We gathered in the small town of Mirik for two nights, at an altitude of 1,495 metres, to help us acclimatise. In the days ahead we would be ascending to 3,601 metres. Mirik’s main attraction is its picturesque lake fringed by pine forest.

Mr CS Pandey takes an early morning cup of tea at Sandakphu. Image: Michelle Hardie

On our second day, we were bused along a winding road to the famous hill station of Darjeeling. I had been told that you need to be brave on Indian buses, but our elderly driver skilfully negotiated the winding road, taking great care on the blind corners. I got used to the noise of his continual horn-blowing to warn other vehicles. ‘Safety is gainful, accident is painful’ read one of the traffic signs.

The first day of racing began in the village of Maneybhanjang, about 70 kilometres from Mirik. We arrived to a festive atmosphere, with flags and colourful HRT banners marking the start line of the event. Crowds of curious onlookers lined the road and local musicians played bagpipes and drums. There was a sudden hush as the Tibetan blessing ceremony began. Then HRT director Mr CS Pandey, who has run this event like a well-oiled machine for 29 years, began the countdown. We were on our way…

Tailoring is part of Indian culture – this man was busy in his shop on the main street of Rimbik. Image: Michelle Hardie.

The 38-kilometre stretch from Maneybhanjang to Sandakphu is a known killer – the altitude rises 1,589 metres. For most of the way it’s the old jeep track that marks the border with Nepal, dating from 1948 when British India split into independent states. As it snaked up to open plains and grassy slopes, the air grew thinner and thinner and my oxygen levels lower and lower. I was walking like a chameleon, hovering each leg in the air with each step, trying to ensure that my feet gently touched the surface. In my semi-confused state, I thought the less impact I made on the road the easier it would be. At some point, mythical creatures danced ahead of me. My head hurt, and then it didn’t. I felt like throwing up, and then I didn’t. Altitude plays silly buggers with you.

Luckily for us walkers, our first-day ended at Garibas aid station from where we were driven the last 16 kilometres up to Sandakphu along a very rough switch-back road. It was dark and freezing and we passed a few runners with head torches illuminating their final ascent.

Mansi Pandey holds the flag for the final day of racing at Palmajua. Image: Michelle Hardie

Sandakphu is a tiny settlement bordering Nepal that provides shelter for trekkers. About 18 Indians live here, permanently employed by the government to manage the accommodation which consists of several dormitory-style wooden trekker’s huts. The one I stayed in was painted a cheerful blue, and was just a few steps away from Nepal.

It was clear enough on the first morning to see three of the world’s highest mountains: Kanchenjunga, Lhotse and Makalu. Sadly, Everest was hidden by cloud. By mid-morning Sandakphu was shrouded in fog and by afternoon hail fell, followed later that evening by a sprinkling of snow. The weather and altitude didn’t stop locals playing football on a small field just behind our hut. That night it became a sleeping ground for a herd of yaks. I huddled near the furnace in our hut’s sitting room. It was so cold that just walking from the bedroom felt like icicles were shifting around in my clothes, touching my skin. At some point, I thought my toothpaste was moisturiser. It took me a while to register what I was trying to lather in my hands. ‘It’s the altitude – it makes people a bit crazy and confused,’ Mr CS Pandey’s super-organised assistant Mansi pointed out.

It was worth getting out of bed at 4.45am in the bitter cold at Sandakphu to watch the sunrise. On a clear day, Everest, Lhotse, Makalu and Kanchenjunga mountains are visible along the Himalayan ridge in Singalila National Park. Image: Michelle Hardie.

The effects of being at high altitude started to wear off as we continued our journey to Rimbik early the next day. The route took us through the dense tropical forest of Singalila, full of rich vegetation – thick tunnels of bamboo, giant-sized rhododendrons, lines of beech trees and towering pines. The singing cicadas made me think of home. The descent was so dramatic (from 3,601 to 1,936 metres) that it took hours for my ears to stop ‘squeaking’.

A Hindu pandit (religious teacher) waits for his train at Darjeeling railway station. Image: Michelle Hardie.

Our hotel in Rimbik, run by Tenzing Chombay Sherpa and his family, was a haven. It had Western toilets, hot showers and excellent food. The dining room with views over the mountains to Sikkim reminded me of a Swiss chalet. I could have stayed a week. Sadly, we only had one day there, a rest day for walkers to take it easy and explore the small town. I jumped into a jeep to watch the runners en route to a tiny village called Palmajua. Laxman Singh, a 21-year-old student who had never taken part in a race before, was cleaning up the field. He was so fit that he crossed the finish line without a sweat. By the end of the trip, we were all in awe of his raw talent and humility. After each stage race, while his fellow runners lay around recovering, Laxman, who was also an HRT staff member, was doing his duties around camp with the rest of the team.

Inside the trusty HRT bus, with driver Pradeep Kumar, Mukesh Sarwal (front), Nirmal Kumar and our youthful guide Ravi Shekhar Pandey (right). Image: Michelle Hardie

My walking companion during the trip was Clare Janty (her sister was running). I had befriended her when she stopped on race-day one to put on her bra. With the crack-of-dawn wake-up call and excitement to be clothed and ‘breakfasted’, she had forgotten its importance. While we walked, we chatted and stopped to look at every mountain and valley view, and at every photographic opportunity we hoiked out our cameras.

As walkers, we were accompanied by guide Ravindar (Ravi) Shekhar Pandey. He became our constant companion with his cousin Shivani, also a walker, who stayed close to his side. Ravi kept a watchful eye on us, slowing his pace so we were always ahead of him. He had a worried expression throughout the walks, but ensured that we weren’t run over by cars coming around blind corners and didn’t fall into one of the steep ravines that lined the narrow twisting roads.

Clare Janty leads the walkers en route to Rimbik. Image: Michelle Hardie.

‘How far have we got to go, Ravi?’ I’d ask. ‘It’s around the next corner, ma’am,’ he’d answer. His encouragement was endearing, even though an hour later we would still be walking. Although our routes were much shorter, we arrived at each destination long after the runners came in.

The final race day took us from Rimbik back to Maneybhanjang. Walkers were dropped off by bus at Dhotre ahead of the runners, who eventually caught up and sped past us to get to the finish. After an exhausting 17 kilometres, Clare, Shivani and I linked arms to cross the line. We came in so late, all the cheering school kids had gone home.

Going from the clean Himalayan mountain air to Delhi’s pollution was a brutal transition. HRT had booked us into The Ashok, a large hotel in the heart of the city. Our last two days were busy, with a day trip to Agra to see the Taj Mahal and a tour of New Delhi.

Back on South African soil, the sky was blue and I could smell the fresh air just as I had in the Himalaya, but my eldest sister wanted more intrigue than my weather report. ‘So did you find Dilip?’ she laughed.

‘I found “Dilips” everywhere!’ I said. ‘I saw him in the eyes of the people, in the stillness of the mountains, and I fell in love all over again.’

Plan your trip

Getting There

I flew to Delhi with Ethiopian Airlines (about R8,000 return). From there, I flew Air India to Bagdogra International Airport (R1,520 return).

Need to Know

The event is held annually in early November. Online visas for South African passport holders are free.

HRT Itinerary

Day 1: Mirik (1,495m)

Accommodation is at Hotel Sadbhavana.

Day 2: Mirik & Darjeeling (2,134m)

Optional tour to Darjeeling which includes a 10km ride on the World-Heritage-accredited Toy Train.

Aid-station energisers. Image: Michelle Hardie.

Day 3: Sandakphu (3,601m)

Race Day 1

Starting from Maneybhanjang, runners cover 38km to Sandakphu and walkers 22km. Accommodation is in trekkers’ huts. A bucket filled with hot water is your shower, and meals are generous.

Day 4: Sandakphu

Race Day 2

This is a 32km out-and-back day for runners through Singalila National Park. The terrain is mostly cobblestones. Walkers can have a rest day or walk to Chandu Lake (20km return).

Day 5: Rimbik (1, 936m)

Race Day 3

Runners take on the Mount Everest Challenge Marathon (42km) from Sandakphu to Rimbik – a technical descent that drops 1 ,220m, with difficult surfaces to navigate. Walkers take a 16km route through the forest in Singalila National Park.

Day 6: Palmajua (2 ,000m)

Race Day 4

Downhill and then a long climb takes runners from Rimbik to Palmajua for 20km, after which they’re bused back to Rimbik. Walkers have a rest day. Evening entertainment is put on by locals doing Nepalese and Tibetan dances. Accommodation is at Sherpa Lodge.

Day 7: Maneybhanjang/Mirik

Race Day 5

Runners start from Palmajua and finish the final leg (27km) at Maneybhanjang. Walkers cover 17km. Lunch is served in the local hall, and then everyone hops on the bus to Mirik for the awards ceremony and final night.

Overall 2019 winner: runner Laxman Singh. Image: Michelle Hardie

Day 8: New Delhi

Transfer to Bagdogra Airport in Siliguri to fly to New Delhi. Two nights at The Ashok Hotel.

Day 9: Agra

Trip to the Taj Mahal in Agra. Lunch at Crystal Sarovar Premiere Agra hotel, and then a tour of local carpet-makers.

Day 10: New Delhi

A tour of the city which includes historical sites such as Raj Ghat, Mahatma Gandhi’s Memorial, plus a wander through a flea market and shopping.

Cost

The 10-day trip includes airport transfers, transport to and from race start points and finishes, accommodation, all meals, food and bottled water at aid stations, plus a day trip to Darjeeling, Agra and a New Delhi tour. From R23,176 pp. (with group discount). Each participant is asked to contribute a $60 (R860) tip for the 300 staff involved in the day-to-day running of the event. himalayan.com

Gear to go

Ram Mountaineering (rammountain.co.za) sponsored the following gear (pictured below):

Black Diamond Fineline Stretch Rain Shell, R2,199

Wind-and waterproof, this lightweight shell kept me super-warm and dry.

Black Diamond StormLine Stretch Rain Pants, R1,699

These were extra-stretchy, comfy and stylish.

Vango Stryd 22 Grey Backpack, R665

This pack was a good size for our long day walks, with comfortable shoulder straps and a supportive chest strap.

Lifeventure Trek Towel, R349

It dried extra fast – much quicker than a traditional towel.

Lifesystems Heatshield Blanket, R149

This retains 90% of your body heat. I stowed it in my backpack for emergencies.

This article was first published in the February 2020 issue of Getaway magazine.

Get this issue →

All prices correct at publication, but are subject to change at each establishment’s discretion. Please check with them before booking or buying.